This is the third installment in my series on the problem of pain. (It starts here and continues here.) In this post I will examine the Biblical story of the fall of man, which purports to explain how suffering became a part of the world God once called good.

The Bible tells us that God intended the world to be a sort of paradise. The description of this paradise is very helpful to a discussion of suffering and evil, because it serves as a vision of a perfect world - a world created by a loving and powerful God. If we accept this description as a part of the Biblical explanation for the existence of suffering, we need not further ponder or debate what a perfect world would look like, we need only determine whether the explanation of how this original paradise decayed into our present world is reasonable.

The Bible does not describe Eden in detail, but it does imply something about it that I find very interesting. As God goes through his creating process he repeatedly stops to remark that it's all very good. The last time he says this is after he has created everything, including plants, animals, and humans. But just before giving this final expression of approval, he tells man that all the plants on earth are his to eat. But they're not just his - they're for all the animals too. Presumably, God thought it would be best if animals weren't killed for food. I recently watched Jurassic Park, and I'm inclined to agree with him. Animals hunting and killing each other is a ghastly affair. The writer of Genesis, along with other Biblical authors, was clearly of the opinion that creating animals which eat each other alive would be inconsistent with the character of a loving God.

For the modern reader, who has at least heard of old earth, theistic evolution, etc., the obvious question is whether all animals really were herbivores before the fall. If animals hunted and killed other animals before humankind came into existence and sinned, I can't see how Adam's fall or subsequent human nature can possibly be blamed for all that suffering. (Of course there are other possible explanations, which I will discuss in subsequent posts.) But if you believe in a literal six-day creation, the Garden of Eden, universal vegetarianism and so forth, it still strikes me as exceedingly odd that God would create animals which are specifically and meticulously designed to be killing machines, since his intent was for them to remain herbivores forever. Isn't the incredibly adapted anatomy of living things the whole platform of creationism? If cheetahs and crocodiles and velociraptors sat around in the Garden and ate grass with cows and sheep, what does that say about their design?

I think the most obvious counterargument for young earthers is that predators were changed after the fall, in the same way that snakes and thorns and the pain of childbirth were changed. This is certainly possible. If there was no death before the fall (which presumably happened soon after the 7th day) there would be no fossil evidence of the pre-carnivorous versions of modern predators. But then the question arises of why man's downfall would have such a radical impact on the rest of nature - not only the physical alteration of innumerable species, but also (it would seem) the beginning of disease, natural disasters, and even death itself, throughout the whole world. Are all these great evils natural, cause-and-effect consequences of human sin? What happened when Adam and Eve bit into that fruit?

The forbidden fruit seemed to have an immediate effect on Adam and Eve - they realized they were naked, and felt ashamed. But what else happened at that moment? Apparently nothing worth recording. The kids weren't really in trouble until Dad got home. And what does God say when he finds his children have disobeyed him? Does he explain to them the natural consequences of their actions? Does he tell them how their disobedience has set in motion events that will destroy them and their world? Or does he curse them?

I don't know Hebrew, so I can't say this with any great authority, but I find the wording of the curses in Gen 3 very interesting. They read not as God listing the natural effects of sin, but as God listing his punishment for sin. God says "I will put", and "I will greatly increase", as if he were a judge handing down a sentence. He also banishes Adam and Eve from the garden. So it seems to me if we're going to take a Biblical view of the beginning of suffering, we ought not to say that suffering is a result of sin, but that suffering is God's punishment for sin. At least, some suffering is. I don't think instances of pain resulting from cruel or selfish human acts can be traced back to these divine curses (unless our sinful nature itself is a curse from God), but at the very least, toil and the pain of childbirth can be.

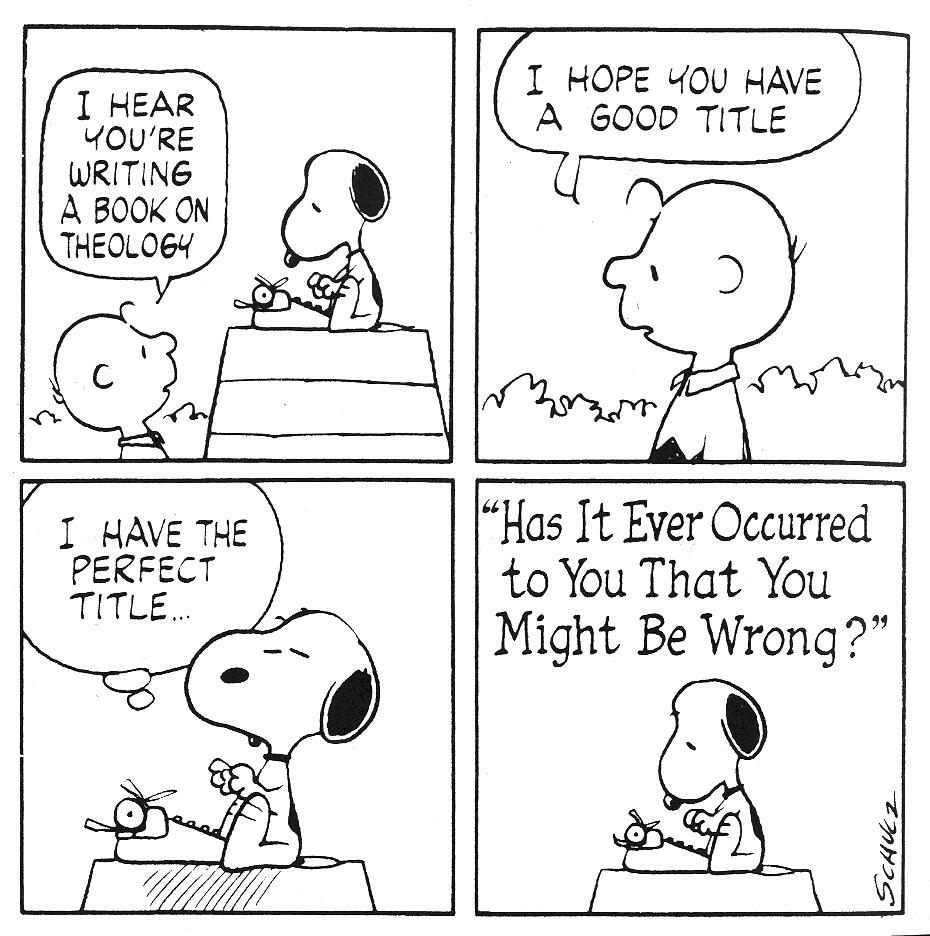

Which raises an interesting question about the exact relationship between the fall and suffering. Just how did the first sin make such a mess of the world that it even brought into existence diseases, natural disasters, and carnivores? I can't say this for certain, but such things (if indeed they can be associated with the fall) would seem to arise not as natural results of sin, but as the punishment of God on all of creation for human sins. God cursed the ground to make farming toilsome; it seems that he also cursed the water and the air to create tornados and tsunamis. God created thorns as punishment; it seems that he also created deadly viruses. God put enmity between humans and snakes; it seems that he also put enmity between wolves and lambs. Or am I wrong?

This is not to say that God is to blame for the fallen nature of the world, only that he seems to have caused it to fall as punishment for man's sin. I don't understand why he would do that, but it does seem consistent with other things God has done, such as commanding the Israelites to slaughter enemy tribes' livestock, in addition to all human members. Another example of this sort of blanket punishment would be sending a flood to destroy all life on earth. If God really wanted to wipe out every man, woman and child in the world (save for one family) because of their great sin, there are numerous ways this could have been done - plague, war, fire from heaven, or simply striking them all dead. But he chose to flood the earth, drowning not only every human, but every animal as well (again, except for 2-6 of every kind). Why?

There seems to be something inconsistent, to me, about the Biblical God's attitude towards animals. On one hand, scripture takes the position that a perfect world would not include violent death for any creatures. On the other hand, animals are routinely caught in the crossfire of God's punishment of humanity. I can't understand this.

I'm afraid I've stumbled back upon an old problem of mine: the Biblical portrayal of God's judgment, which is radically out of sync with my own intuitive understanding of justice. In the Bible nations are judged and destroyed as a whole, children are punished for their ancestor's sins, and (based on the above) animals are cursed for the disobedience of humans. Of course, in everyday life the consequences of misdeeds are commonly suffered by those who did not perpetrate them - children, families, nations, and animals. This is both a natural part of our world and a significant aspect of the problem of pain. Although we see it every day, we sense that something is wrong - very wrong - about innocents suffering as a result of other's sins. The Bible (at the least, this portion of the Bible) does not explain how God could allow undeserved suffering. On the contrary, it makes God a perpetrator of such suffering.

I want to be clear: I'm not trying to find fault with the Biblical God or tell him that he should to have acted differently. What I'm saying is that his actions, as I understand them, make no sense to me. I recognize that this is not a particularly persuasive argument against the existence of the Biblical God. Please understand, it's not intended to be. What I'm saying is that any explanation for the existence of suffering in God's creation that requires a literal interpretation of the Bible is extremely unsatisfactory to me. Unless my readers wish to change my mind, I will move on to other possible explanations for the existence of suffering.

[+/-] The Bible on Pain |

[+/-] Not Especially About Pain |

I recently came across this post in draft form. I wrote it almost exactly one year ago, and I don't know why I never published it. I like it, and I think it relates to some of my more recent thoughts. Some parts of what I've written here have changed in the past year (for example, I'm not nearly so bitter with God, and it turns out my hair does look good long) and other parts have stayed the same. I still think it's interesting, but then, I'm probably more interested in my own out-of-date thoughts than anyone else. My next post about pain is nearing completion, but in the mean time, this is me a year ago:

It's Christmas time, I'm off school, and come to think of it, today's my birthday. But none of this is particularly exciting right now. The world is cold and grey. I don't know what I believe, but I know it's not what I want to believe. I'm confused, and I know I'm not smart enough or diligent enough for this task. God seems not to be on side, and that doesn't help. I feel at peace about the process I've engaged myself in - the process of questioning and fighting through my faith. I know this is what I should be doing, but I also know that I cannot do it well. I know that I'm too emotional, too lazy, too tired and skeptical and too human to find God or truth. So the problem is not that what I'm doing is wrong, it's that I am doing it poorly, and I cannot do it better. I've been dwelling a lot on hell, and I don't know how much of what I've written on this will ever be published here, but it's fairly discouraging.

What I've read in the past 24 hours: part of an old book about why the KJV is the only Bible translation you should read, and parts of another book about why the Charismatic movement is bad and miracles ceased after the NT was written. Neither seemed particularly well thought through or honest.

Random stuff: I'm thinking about people I know, and their various viewpoints. I talked to a girl the other day who is no longer a Christian, and who says that rejecting Christianity was the most wonderful, uplifting experience of her life. I talked with my relatives about Christianity and the Bible, which they hold to be the inspired word of God. I talked to various people about hell, and how to reconcile the doctrine of hell with my beliefs about God's goodness. I talked to friends who are struggling with the church, friends who are walking away from the church, and friends who embody the church. I talked with a few people about how the direction I'm headed will cause me to be more and more detached from the church, simply because I will be less and less able to volunteer in Christian ministry. I was kissed twice this week: once by my grandma, who's in the hospital, and once by a mentally ill homeless man. It's 5:00 right now, and it's cold and dark out. I have a party to go to tonight. I generally hate parties, but I was at a good one the other day. People are dying in the world today. I'm feeling melancholic, and I'm not wearing socks. It looks like Hotel Rwanda may not be playing in Edmonton. Has anyone talked with God lately? How is he doing? I hear he might be in Africa. I don't think I really like him. He's done a lot of bad stuff in the past, and he doesn't seem to be sorry for it. He's pretty icy, hard to get close too. I think I may resent the fact that he's the center of my life. Everything I think about and do revolves around him, and he knows it. I wish I could go a day without thinking about God, just living, loving, doing stuff, and not bothering about prayer or ethics or the problems in Jude. I wish I could just be myself and sort of have my own ideas about God and religion that don't come to the surface unless someone asks me about them. And then I could think for a bit and explain some of how I feel about God and stuff, and we could chat about it or whatever, but it wouldn't be me, you know? It wouldn't be what I'm all about.

I think one of the big problems with me is that I'm afraid of hell. I guess most people are, but it's so stupid. Just do your best - that's all you can do. And maybe someday when you're dead God will say "sorry, you thought the wrong stuff, so damn you", or maybe he won't. He chose not to make this straight-forward. That was his choice, not mine. I can't get myself all bent out of shape about something I really have no control over. If I wasn't afraid of hell, I think I could do a lot of things with my mind.

One thing I really value in my friends is their differences. I have friends that are a lot like me, and others that are so different. I grow when I interact with them, because they stop my thoughts from becoming inbred and redundant. But I wish I had more diversity in my friends. I don't make friends easily, is the problem, but if I had my choice I'd have Mormon and Jewish and Muslim and Catholic and atheist friends, and gays and feminists and humanists. I'd have some friends that were really smart, but others that weren't. Some of my friends would be open and tolerant and great to talk to, but others would be closed-minded and a little irritating. Some of my friends would like to go to coffee shops, and I'd go with them and talk about global responsibility and philosophy and love. As long as I'm wishing, I'd also like the taste of coffee and Chinese food. My hair would look good long, and I'd be able to play the guitar. I'd probably have a girlfriend.

(That was a segway.) I found myself wishing I had a girlfriend the other day. Not in a "oh man, I need get a girlfriend soon" way, but in a kind of whimsical, "some day it would be cool" way. My girlfriend would be smart and honest, and I'd think she was very pretty, though she wouldn't believe me, because girls are weird like that. She'd be someone who I could be very, very real with. She'd know me better than anyone else; she'd be like the second me. She wouldn't know me perfectly, because that's impossible, but she'd know me about as well as I know me, and she'd have a different view of me, and I'd come to her to try to find out who I am. She'd play the piano, I guess. Or the guitar, but I'm already pretending I play the guitar. I don't care, it could be the other way around, or maybe one of us plays the violin or something. But it couldn't be a wind instrument, because you have to be able to sing while you play. I would lie on my bed reading poetry by candle light, and she would come over without calling first and practice her violin, playing sad songs and singing in French, and I'd pretend to keep reading, but I'd just listen to her voice and her violin making beautiful sounds I didn't understand, and she'd know I was listening more than reading because I'd start to cry. I just wish I had a #1, you know? A best, best friend, but more than that.

I think the god-shaped hole is a myth. I think we have a something-shaped hole, but no one really knows what the shape is exactly. I doubt anyone's ever done a good job of filling this hole with God. Not that God couldn't fill it, maybe, but he doesn't. He just sits up there and does whatever he does (probably holds the world together or something) and he's not that interested in filling your hole.

[+/-] The Problem |

The problem of pain is a simple one. We know it intuitively. In straight-forward terms it is the question of how terrible suffering can exist if there is a loving God. The more philosophical-sounding way of stating it is this:

1. God is omniscient (knows everything)

2. God is omnipotent (can do anything)

3. God is omnibenevolent (is completely loving)

4. There is gratuitous suffering (suffering without any good reason)

All of the above cannot possibly be true. If people and animals suffer without any good reason, then either God does not know about it, or he is powerless to stop it, or he does not love us, or he does not exist. Those are the only options. (It is taken for granted that a being who loves another will not wish his/her beloved to endure gratuitous suffering.)

Clearly, this presents a huge problem for people who believe in God. No one can deny that there is a lot of suffering in the world. No one can deny that this suffering often appears to have no positive effect, or at least, to have far more negative effects than positive. So what do you do? If you're dead set on believing in God (or if you find the arguments for God's existence so convincing that they overwhelm any counterarguments) you basically have two options. You can say that all suffering, no matter how terrible and senseless it may appear, has a sufficient purpose, or you can say that God is not aware of this suffering, or can do nothing to prevent it, or simply doesn't care.

The first option is certainly more appealing, if you're fond of the omni-everything concept of God. Some have tried to explain how all pain has a purpose, or at least, how it is conceivable that all pain may have a purpose. Failing that, most theists will want to put some limit on God's omnipotence by explaining how God cannot break certain laws (for example, human free will) and is thus powerless to prevent suffering. Few will wish to say that God is not aware of our suffering, because this makes him very weak and uninvolved. A few might challenge God's omnibenevolence, saying that perhaps God is so repulsed by our sinfulness that he pours out his well-deserved wrath upon us in the form of suffering. And if all of this fails, there is always Atheism. Also, it should be noted that this problem can be solved by positing two or more Gods, one of whom is malevolent or sadistic.

One final response is worth mentioning. Many people (in fact, I think the majority) say they simply are not capable of finding the solution to this problem, but they cope better with suffering by believing in a loving God, and they will therefore choose to have faith that the existence of a loving God is not inconsistent with the immense suffering, though they cannot imagine how. This is certainly a respectable position. Indeed, if we conclude that we are unfit (because of lack of evidence or insufficient intelligence) to render a verdict on this matter, it may be the most responsible position. But I'm getting ahead of myself.

This post is intended merely to introduce the problem and list the main types of responses to it. I intend to expand on and critique most or all of these responses in subsequent posts. I appreciate the reading suggestions my readers have offered, but I doubt I'll have time to read many of them. However, I believe that I'm familiar with most of the arguments presented in these books, though perhaps not in exactly the same form, and I fully intend to address each of them. I trust that my readers will alert me if they feel I have overlooked, misrepresented, or too quickly dismissed an important position.

[+/-] Next Up |

I think the next major thing I'm going to think about is the problem of suffering. We discussed it briefly in my Philosophy of Religion class, and I realized that I don't understand why there is gratuitous suffering in the world, and I cannot at present reconcile this with my beliefs about the nature of God. Thus, it behooves me as a philosopher to confront this inconsistency in my beliefs and attempt to resolve it.

Here's my ever so tentative schedule of what to think about:

1. The problem of pain - what it is, why it's a problem. I think I've got a good start on this.

2. The Biblical explanation for the existence of pain - the fall, etc.

3. Other Christian-ish explanations for pain. (That is, explanations that are consistent with my understanding of God.)

4. Not-so-Christian-ish explanations, including atheistic ones, if necessary.

I intend to blog as I go, both because writing helps me gather my thoughts, and because I'm interested in your thoughts on this issue.

[+/-] What God Is Not (A Theography) |

I love the idea of theography (writing about one's personal experience with God), as opposed to theology (making claims about the nature or character of God). I love the humility of theography, which seems to say, "I don't understand God, and I cannot create definitions or concepts that accurately portray who God is. All I can tell you is my own experience with God, which need not be in competition with yours." The theographer is less interested in catching and canonizing some truth about divinity than in receiving gifts of wonder and beauty, and sharing these gifts with others. I want to do theography.

My problem is that there is little or nothing in my life that I think of as experience with God. Regardless of it's cause, this absence of experience makes theography somewhat difficult to do. It seems to me that I can talk with far more certainty about what God has not done in my life than about what he has done. Hence, if I am to present a theography, it must be a negative one. (I mean negative in the sense of focused on what is not, rather than what is, not in the sense of pessimistic or overcritical, though I fear some of you will take it that way.)

Please note: I will use the words "God is not" to mean "I have personally experienced God not to be" or "I have personally come to understand God not to be". I recognize that this may make my statements sound dangerously authoritative (that is, theological), but I stress that I do not intend to convey anything beyond my own personal and highly subjective experience. Perhaps it would be better if I used one of the latter expressions, but they're just so damned unwieldy. Anyway, here we go.

God is not a vending machine. He is not an electronic salesman, hawking joy or blessing or Spirit-power like OhHenrys in school hallways. No proper ritual of prayer and desire and tithing and good deeds can produce my desired results in the manner of D-5 and one dollar. God cannot be predicted. God cannot be bought. God does not come with instructions, and he does not offer refunds. God is not a vending machine.

God is not a promise. I cannot "test him in this" - not for wealth, not for guidance, not for good gifts, or the Spirit, or the movement of mountains. God does not come with special offers or complimentary gifts. God is not a policy or a contract, and he cannot be brandished to ward of pain, nor presented to gain access to pleasure. God is not a promise.

God is not answers. He presents no special insight into science, politics, or ethics. He endorses no worldview. He reveals no plans. Seeking does not beget finding. Supplication does not beget response. Study does not beget infallibility. God is not answers.

God is not my friend. He does not offer companionship, he does not he share his life with mine. God is not touch, heat, or arms to hold me. God does not confides in me. God will not come to me when he's hurt or confused. He will not hang out with me, or write me e-mails, or buy me coffee. God is not nearness or oneness or a kindred spirit. God is not my friend.

God is not my father. He does not hold, guide, instruct or inspire. A father must be more than the cause of my existence. A father must be more than a benefactor, more than an authority. A father who has no time to spend with his child is not a father. A father who does not talk with his child, comfort him, listen to him, or laugh with him is not a father. God is not my father.

So there you go. Once again, that's my experience. It's not meant to contest with yours. It's also not meant to evoke any particular emotional response, nor is it meant to sound bitter or whiny or accusatory. If it comes across somewhat differently than it was intended to (and it does, at least to me) I suspect this is a result of the reader being conditioned to think of experience with God within very narrow parameters. I present this theography partially because I think it's beneficial for us to question such parameters.

I welcome you to respond with your own theography (or any comments you have about mine). You may use any style or format that you wish, and you need not address any of the points I've touched on. What's your experience with God?

[+/-] Further Further Reading |

"Love is my Faith and my religion and wherever its caravans take me, that is where I shall follow, for love is my religion and faith."

This is what I'm all about. Thanks to Bruce.

And as long as I'm recklessly throwing out links to all and sundry, I'd like to draw your attention to and/or further ballyhoo the already much ballyhooed new blog written by my good friend Jonas (of left-an-interesting-comment-on-my-blog-recently fame). He is a self-described "towering talent", whose writing is rumored to be "charged with whimsy, humor, and (occasionally) pictures of babies dressed up as potted plants". Moreover, he promises "words that will fill the ache inside". While I am naturally skeptical of such lofty claims (cynic that I am), I know that if anyone can deliver on such a promise, it is he.

That ringing endorsement should be worth at least eight bucks.

[+/-] Further Reading |

I got an e-mail recently from a guy named Jim Johnson, requesting that I link to his blog, Straight, Not Narrow (a splendid title), presumably because of my recent post about some Christians' un-Christlike treatment of homosexuals. I read some of his stuff and decided it was worth a link. If you're interested in the whole homosexuality/Christianity thing, he's got enough links to keep you busy for a while.

Also well worth reading is this blog, written during the coming out of a gay Christian blogger. (His current blog is here.)

And if I could prevail upon you to read one thing about homosexuality, it would be this excerpt from the book A Place at the Table, which challenges a very prevalent stereotype about homosexuals, as well as taking issue with the "just don't flaunt it" school of tolerance. Unfortunately, the book is friggen impossible to find in Edmonton. I may have to break down and finally buy something on line.

Happy reading.

[+/-] Clarification |

This post is partially a response to this comment by Jonas. A number of comments I've received lately have made me realize that the impression some of my posts have made on some readers are quite different from what I intended.

I think there are a couple of writing habits I've fallen into that have apparently given some of my readers the wrong impression of my views. For one, I sometimes use "Christians" as a sort of shorthand for "some Christians, of whom I am one", giving the impression that I'm lumping all Christians together, and then distancing myself from them. I've received comments to the effect that I must know some pretty horrible Christians to be so frustrated and disillusioned with them. I don't think this is the case. When I criticize those Christians (who are by no means representative of all Christians) who scorn or mistreat "sinners", over-emphasize the Bible, are intellectually dishonest about the nature of their God, or engage in self-centered "worship" (to name a few recent tirades), I am criticizing what I personally once thought and did, or in some cases still do. I'm well aware of how easy it is to criticize those who are different, which is why I try not to write about Muslims, Atheists, Calvinists, Catholics, or baseball fans. I'm sure some people within these categories (who are not necessarily representative of everyone within their respective categories) are in error on various points and ought to be corrected. But I am none of these things, I know little or nothing about them, and thus I am in no place to critique them. I will only ever critique myself and those like me - that is, views that I have held, or things I have done. At least, this is the standard I try to hold myself to. In the future, I will try to be more clear that I don't disagree with all Christians (how absurd) on any certain issue, and I can relate to those Christians I believe to be in the wrong. I can understand their thinking (to a point) and I can sympathize with them because I once thought as they do, and, in many cases, still act as they do.

Jonas is right that I have more difficulty loving judgmental, holier-than-thou Christians than homosexuals. I won't pretend I don't struggle with this. However, being a recovering judgmental, holier-than-thou Christian myself, I have a reasonable understanding of their mindset and actions. Although I often become frustrated with certain segments of Christianity, I seldom feel malice towards any individual person.

However, what I feel is not the issue here. It is one of my weaknesses as a writer that I tend to forget or downplay the effect my words might have on the reader. What in my mind is a very calmly reasoned (yet forcefully presented) argument against a faceless ideology may be read as a personal attack against cherished beliefs, or a bitter rant against an enemy. Unfortunately, my passion as a writer occasionally exceeds my diligence as an editor, and I think I can come across as more angry and judgmental in writing than I would ever be in person. Like Paul, I tend to be timid when face to face, and bold when away. Of course, it's far easier to be gentle and understanding when face to face with a human being (however pharisaic) than when confuting a perceived distortion of the Gospel through a keyboard.

I certainly appreciate the comments I receive, particularly the ones asking for clarification or expressing disagreement. Such comments are half the reason I blog. (Half? Maybe 30%.) If you think something I've written is grade A bullshit (or even grades B through D bullshit) please let me know. And if you agree, you're allowed to tell me that too.

[+/-] What Should Have Been Done |

A bunch of Christians should have looked around them a few decades (or centuries) ago and said "Hey, we see a group of people who are marginalized. They're afraid, they're misunderstood, they're feared and ostracized and discriminated against. It isn't right that they should be treated like this. We should help them." And then the Christians should have approached these other people and shown kindness to them. Not bullshit pretend-to-be-their-friend-so-they'll-listen-to-your-sales-pitch kindness, but the sort of kindness Jesus showed. The kind where the other person believes that you sincerely care about them, where you give of yourself freely and unconditionally. The kind where you stand up for them against adversity, and also sit down with them in fellowship. The kind where you spend a lot of time listening and not much time talking, where you don't pretend to understand the other person - their thoughts, feelings and motivations - until you've earned that understanding through long years of intimacy. The kind where you don't judge.

Some of these Christians - the ones who were politically motivated - should have organized rallies and wrote letters to raise awareness about the mistreatment of this other group. Some who were leaders should have organized charities and ministries to help those among them who were struggling emotionally or physically. Some should have organized support groups including both Christians and members of this other group, and many should have just hung out together.

Few Christians should have dwelled on whether what these people were doing was right, or whether membership in Christianity and this other group are mutually exclusive. None should have preached to them about their sin. None should have resisted the fight for their recognition and rights. None should have opened their mouths against these people as a group before first knowing and loving them as individuals. None should have shamed them, or excluded them, or seen their choices or their lifestyle before their humanity. This other group I'm talking about is homosexuals, but the same thing applies to any other group that faces bigotry.

I've gone from "being gay is wrong" to "being gay is not wrong" to "who cares whether it's wrong or not". Seriously, why does it matter? Why should a person's lifestyle and the question of it's sinfulness have any effect on the way we interact with them? If Christians want to concern themselves with society's acceptance of homosexuals, they should be fighting against discrimination and bigotry, not perpetrating it, regardless of their personal views (or even God views, if you're so confident that you know what they are) about it's rightness or wrongness. It's as if Christians feel that their first responsibility in relating to "sinners" is to make it clear to them and anyone else who might be watching that they disapprove of their "sin", and their second responsibility is to show God's love, so long as it doesn't interfere with the first. What nonsense! Love people first, and then if you really feel led to make them aware of their sin, you'll have the opportunity sooner or later. (And this way you'll actually know what you're talking about, and they might even be inclined to listen to you.) But remember that our responsibility in the world is not to convict people of their sins. That's the Spirit's job. We're here to show love - without restrictions, without conditions, and without concern for what the upright and the uptight will think.

[+/-] A Gold-Foil Idol |

My Art History teacher recently mentioned that Christianity is a text-based religion, meaning that it's built around a book. I don't think I like the idea of text-based religion (or "spirituality", if "religion" is a dirty word to you). I think text is good (I'm a student, remember. I know the value of books.) but I don't want the focal point of my life to be a book. I want the focal point of my life to be servanthood, selflessness, and love.

After thinking about this a bit I decided many Christians would agree with me. I'm sure that many would say their religion may be text-based, but it's not text-focused or text-contained. They would say that they too pursue love as their highest goal and that they've found the Bible to be an indispensable guide in this pursuit. I certainly have no objection to that. What concerns me is that all too often text-based becomes text-focused, or doctrine-focused. The logic seems to be that if a book is our basis, then proper understanding of this book must be our goal. This is tragic, because it turns Jesus' revolution into just another brand of Phariseeism.

Jesus was all about people. He healed people, he fed people, he taught people. But more than that, he went to people's parties, he stayed up late talking to people, and he spent time with the people no one else in his society cared about. And I don't have to tell you that the one group Jesus didn't get along with was the doctrine-obsessed religious elite. It wasn't their vast knowledge of the scriptures that Jesus objected to, nor their zeal for righteousness - these things are of course good. But their lack of love, their obsession with their own legalistic purity, this Jesus found intolerable.

When Jesus was gone his followers wrote down the things he said and did. Of course they did - how else could this important knowledge be preserved for future generations? But I believe many Christians make the mistake of caring more for the text its self than for what it represents. How is it possible that those who know best the life and teachings of Jesus can become so preoccupied with headcoverings and translations and speculation about end times? How is it possible that such people are more interested in denouncing those they see as sinful than in loving them?

Look through the New Testament. (Do look, because I may be forgetting.) When Jesus met a "sinner", did he first confront him with his sin? Did he reason with him about the wrongness of his actions, or quote scripture at him, or urge him to turn from his wicked ways? Did he place more emphasis on the sins of the "especially bad" sinners than on those of the "pretty good" ones? Did Jesus ever start a conversation or a relationship by making it clear that he disagreed with the other's lifestyle? Jesus came to everyone on their level, he treated them with dignity, he listened to them, he helped them physically and practically, and he didn't condemn. And he certainly didn't give a shit what the religious people would think when they saw him hanging out with sinners and scum.

Jesus was not about the Bible or the church, he was about people. He didn't sit around pontificating about obscure points of doctrine with the ultra-religious, he brought hope and inclusion and practical wisdom to the oppressed and the godless. Jesus didn't hold his nose or hitch up his skirts as he walked through our world and he was more pissed off by self-righteousness than by wickedness. Jesus came to heal the sick; we've pulled him out of the hospital, scrubbed and groomed him, and made him the patron saint of the germophobes. Jesus was not afraid of sin-cooties or guilt by association. And he didn't place any book or doctrine or religion above the sheep he came to save. The minute our high-minded chapter-and-verse piety gets in the way of being the servants of all, we've abandoned the Gospel of Christ for a gold-foil idol.

(On a related note, I just read an interesting modern take on the Woman at the Well, over here. Thanks to Bruce.)

[+/-] What I'm trying to say is this: |

But perhaps I should explain. I've been thinking recently about beauty. I think a lot of my life is a pursuit of beauty - beauty in my actions, beauty in my relationships, beauty in my writing, and so on. I'm using "beauty" rather broadly, I guess, but I feel like there's a strong relationship between visual beauty (and our reaction to it - wonder, I guess) and things like humility, love, wisdom, and joy. Maybe I mean that all good things are just different aspects or expressions of each other, like a single object that is perceived through multiple senses. But I told myself I wouldn't start talking like this.

But perhaps I should explain. I've been thinking recently about beauty. I think a lot of my life is a pursuit of beauty - beauty in my actions, beauty in my relationships, beauty in my writing, and so on. I'm using "beauty" rather broadly, I guess, but I feel like there's a strong relationship between visual beauty (and our reaction to it - wonder, I guess) and things like humility, love, wisdom, and joy. Maybe I mean that all good things are just different aspects or expressions of each other, like a single object that is perceived through multiple senses. But I told myself I wouldn't start talking like this. I've decided I don't like beauty being co-opted as a means to some other end. I feel like theists have degraded the beauty in our lives by turning it into some kind of argument for the existence of God. Not that there's anything wrong with feeling that beauty points you toward God, but by making an argument out of it, by subpoenaing beauty to be dispassionately analyzed and debated in defense of an intellectual proposition seems cold and demeaning. I think it would be better if we could each see beauty and let it influence our minds and hearts as it will, but not try to force those influences on others.

I've decided I don't like beauty being co-opted as a means to some other end. I feel like theists have degraded the beauty in our lives by turning it into some kind of argument for the existence of God. Not that there's anything wrong with feeling that beauty points you toward God, but by making an argument out of it, by subpoenaing beauty to be dispassionately analyzed and debated in defense of an intellectual proposition seems cold and demeaning. I think it would be better if we could each see beauty and let it influence our minds and hearts as it will, but not try to force those influences on others. I hope I'm learning to respect beauty. I remember that I used to have a fantasy about suddenly and inexplicably acquiring the ability to play the piano at the highest level. I have dreams of this nature about all kinds of talents (I suspect they're quite common) but this particular one was largely laid to rest when I got to know a girl who spends hours a day practicing the piano. After that it seemed wrong to want without cost what she has worked so hard for. Love without cost is not love; beauty without cost is not beauty.

I hope I'm learning to respect beauty. I remember that I used to have a fantasy about suddenly and inexplicably acquiring the ability to play the piano at the highest level. I have dreams of this nature about all kinds of talents (I suspect they're quite common) but this particular one was largely laid to rest when I got to know a girl who spends hours a day practicing the piano. After that it seemed wrong to want without cost what she has worked so hard for. Love without cost is not love; beauty without cost is not beauty. Someone is going to think too hard about what I'm saying, looking for a logical argument. But I'm not talking about logic here, I'm talking about beauty. Beauty, as I understand it, is of a different substance than logic - it can be felt and perhaps expressed, but not analyzed, not calculated.

Someone is going to think too hard about what I'm saying, looking for a logical argument. But I'm not talking about logic here, I'm talking about beauty. Beauty, as I understand it, is of a different substance than logic - it can be felt and perhaps expressed, but not analyzed, not calculated. In high school I read a story in which a farm-girl is kidnapped by a lunatic who's obsessed with beauty. At one point, to distract him, the girl points to the setting sun and mentions that it's beautiful. The lunatic's earnest reply is "God Almighty beautiful - to take your breath away!" I've often reflected that if there's one thing I would be unwilling to give up for any reason - even for God - it's my mind. I treasure my ability to think more than anything else. But I wonder if I wouldn't mind being a madman or a fool if I could feel beauty like that.

In high school I read a story in which a farm-girl is kidnapped by a lunatic who's obsessed with beauty. At one point, to distract him, the girl points to the setting sun and mentions that it's beautiful. The lunatic's earnest reply is "God Almighty beautiful - to take your breath away!" I've often reflected that if there's one thing I would be unwilling to give up for any reason - even for God - it's my mind. I treasure my ability to think more than anything else. But I wonder if I wouldn't mind being a madman or a fool if I could feel beauty like that. Sometimes I think knowing beauty is my greatest desire, and sharing beauty with others is my highest calling. At other times the idea makes me feel guilty - my rational mind scolds me for loosing my focus on logic and truth. But I'm increasingly suspicious that the pursuits of beauty and truth are not opposed, nor is one necessarily more valuable or honorable than the other. And maybe beauty and truth are really just the same transcendent object seen from different perspectives. You may call this object what you wish or you may leave it nameless, but understand that no words can accurately convey it's essence. Perhaps it can be best expressed like this:

Sometimes I think knowing beauty is my greatest desire, and sharing beauty with others is my highest calling. At other times the idea makes me feel guilty - my rational mind scolds me for loosing my focus on logic and truth. But I'm increasingly suspicious that the pursuits of beauty and truth are not opposed, nor is one necessarily more valuable or honorable than the other. And maybe beauty and truth are really just the same transcendent object seen from different perspectives. You may call this object what you wish or you may leave it nameless, but understand that no words can accurately convey it's essence. Perhaps it can be best expressed like this:

[+/-] The Paper Pope |

[FYI: This post's original title was "The Evangelical Pope". It was meant to be an immediate sequel to this post from June, but it somehow got forgotten and was only recently rediscovered and completed. I read A Generous Orthodoxy over the summer and it surprised me by addressing the exact same issue, though under a slightly catchier title, which I've decided to adopt.]

I've heard a lot of Protestant Evangelical-types bad-mouth Catholics for the whole Pope thing. I guess they don't like the idea of some guy in a big hat telling other Christians what's right and what's wrong. Christians, each of us being priests of God, each of us being indwelt by the Spirit, need no intermediary to inform us of God's will. We should each be able to pray and consult our Bibles and discern the truth for ourselves. (Never mind that we all disagree after doing so. Those who disagree with me must have unconfessed sin or something interfering with their Spirit-radar.)

About that Bible... Oh, first maybe I should say this again just to cover my ass: I like the Bible. It's a good book, and you should all read it. Of course I don't agree with everything it says (neither do you) but on the whole, it's a really useful - even "indispensable" - tool for learning about God.

That said, I wonder if we've made the Bible into something it's not. Picking up on the Pope thing, my guess is that the Catholics like all their church structure with the hierarchy and the traditions and the infallible Pope because it gives them security. Want to know where you stand on a tough issue? Look to the Pope. Want to know how to do Church? Just do what we've always done. And the really great thing about centralized power is that not only do you know what to believe, but you know what everyone else should believe. No need for infighting, no excuse for schisms, nothing but harmony and solidarity. Sure, it doesn't work perfectly, but it works a lot better than anything those fragmented, infighting, oh-so-aptly-named Protestants have come up with.

With the caveat that I've never actually talked to a Catholic about this particular issue, I imagine the following conversation between a Catholic and a Protestant:

The Catholic speaks first. "I know you're suspicious of my faith in the infallibility of the Pope, and you talk about the dangers of trusting in the judgment of one man on spiritual matters, but isn't it more dangerous to leave these matters up to comparatively ignorant and ungodly individuals? I would think you'd be lost without the leadership of one who speaks for God, just as the judge-less Israelites each did what was right in his own eyes. How can you hope to follow God without a God-ordained guide?"

"But we do have a guide," the Protestant would of course reply. "We have the Bible, our instruction manual for life, which is inspired by God, free from error, and contains everything God needs us to know in order to live as He desires. Furthermore, we each have the Holy Spirit, the Counselor, who tells us how to understand the Bible and apply it to our lives."

"Yes, that all sounds very nice, but surely you can see that it doesn't work. The Bible is a pretty confusing guidebook at the best of times. Look around you! Look at all the denominations you Bible-believers have split into. Each one is convinced that their own understanding of Biblical commands is correct and all the others are wrong. Don't you see that well-meaning Christians can no more agree on the meaning of the Bible than secular readers can agree on the meaning of other books?"

To a certain extent I'm quite happy for people to believe that the Bible is absolute truth and strive to understand and apply it. Generally they seem to miss the ugly stuff and come away with ideas centered more or less around love. Generally.

And yet there are always dangers of taking anything to be an unquestionable authority - regardless of whether it really is infallible - especially when that authority is an inanimate object that can't speak for it's self. First of all, we have a tendency to want to remake the Bible in our own image. (I'm not saying you do this. Heavens no! I mean people less in tune with the Spirit than you are.) It's easy to develop our own opinions and then go searching in the Bible for proof that we're right. Of course, this is usually done subconsciously, but I don't think I need to convince you that it is indeed done. (If I do, please let me know.) What's dangerous about this sort of selective reading is that once we find the verse that supports our (unconsciously) pre-formed conclusion, we believe that our opinion is unquestionable TRUTH. In my opinion, an unwavering, unassailable conviction that you're right may be the most dangerous thing in the world. It naturally precludes any further reflection or scrutiny (why bother with logic when you have the word of God?), and leads to patronizing, scorning or hating of those who disagree (imagine being so misguided/stupid/wicked as not to see THE TRUTH). It's also worth noting that these unpleasant side-effects can accompany unquestioning Bible-belief even if you manage to avoid interpreting the Bible through your own preconceptions. And of course, just because you come in with an open mind doesn't mean you'll leave with the correct interpretation. (Well, I guess many people believe that the Spirit won't allow you to be mistaken if you're sincere, but since this belief tends to be held dogmatically, I'm not sure it's worth my time to argue against it.)

I'm honestly not interested in convincing you that the Bible's not infallible. If you can't live without a "fixed point of reference", the Bible probably as good a choice as any. But please don't believe your interpretation of the Bible is infallible.

[+/-] Heck No At All! |

I was talking to a friend the other night about some of my recent entries and I realized he had entirely the wrong impression of why I think about what I do. At least, he and I disagreed, and I realized that I hadn't made my position as clear as I thought I had. So this is to explain why I write about the dark side of God and such things.

This will sound pretentious, but I read something in Plato's Republic that's analogous to my situation. The character Glaucon challenges Socrates, the protagonist, with a fairly persuasive argument in favor of living unjustly. Glaucon (wonderful name) stresses that he does not agree with the argument he's presenting - he believes, or wants to believe, that justice is superior to injustice - but he has not yet heard an argument in favor of justice that is as persuasive as he would like it to be. For this reason, he presents Socrates with an argument against justice that is as strong as he can make it and challenges Socrates to overcome it, hoping, of course, that he can.

I hope (I'm not certain) it's clear to the reader that I don't have a vested interest in proving God to be unjust. Where would that get me? I really want God to be just, in fact I would do almost anything to continue to believe in God's justice, except ignoring or shrugging off evidence against it. I have long held the conviction that if I am to truly and resolutely believe in something, I must subject it to serious scrutiny. Not a mock-trial. Not a perfunctory, cursory scan of the evidence. I'm talking about honest, diligent examination.

This is why I sometimes write about the wrath of God and other things unbecoming of a devout Christian. Because I don't know anyone else who does, and I take my faith seriously enough to want to discover, to the best of my abilities, whether my beliefs are contradictory or flawed. I have no beef with those of you who find fault in my arguments (that's half the reason I blog) or the presentation thereof. But for those of you who think I'm an apostate, a God-mocker or a recreational doubter, hopefully this clears a few things up. If you still object to the questions I ask, I'm quite willing to discuss this further. And if you still object after that, no one's forcing you to read my blog.

I just remembered I wrote something similar to this a few months ago. I rather liked that post.

[+/-] The God of Wrath |

By now you've probably heard at least one fundamentalist group claim that the flood is God's judgment against New Orleans for Mardi Gras and other such wickedness. Various people have brought these claims to my attention, expressing their horror, disgust, disbelief and so forth, both at the idea of God destroying a city out of wrath and at those who have the heartlessness and gall to suggest it.

These claims of judgment immediately reminded me of a book of apologetics I browsed over the summer (Evidence that Demands a Verdict), specifically the chapter detailing the fulfillments of certain Biblical prophesies. These prophecies turned out to be almost exclusively about the violent destruction of wicked cities.

A quick scan of the prophetic books of the Old Testament reveals a remarkable fixation on judgment. One who reads these books might be forgiven for thinking that God spends most of his time pouring out wrath on immoral cities and nations. In a similar vein are the stories of the great flood in which God drowned all of mankind, the incineration of Sodom and Gomorrah, the ten plagues on Egypt, Joshua's genocidal conquest of the Promised Land, David's raiding parties (in which he left no woman or child alive), and the mass killing at the climax of Esther. If you read through the Bible it's hard not to notice God's habit of pouring out destruction on cities and nations as a whole (to say nothing of punishing children for their father's or even distant ancestor's sins). Mention this to most Christians and they'll tell you something about how God is just, or how it would be wrong not to punish evil people for their wrongdoing, or how actions have natural consequences...

Maybe you think the Egyptians (all of them, as a race) had it coming to them for enslaving the Israelites. Maybe you can explain why it was necessary or even compassionate for Jewish warriors to wipe out whole tribes, down to the last woman and child. Maybe you believe that we are "fallen" and God is holy, and this somehow gives him the right to wipe out "evil" cities. Maybe in your mind this is enough for Tyre, Sidon or Ashkelon. Is it enough for New Orleans?

Watch the News. See destruction. See grief. See the dead, the dying and the desolate. See the rich in safety and the poor in misery. See the statistics, and then see the people who make them up. See chaos. See despair. See the ruin and carnage created by a hurricane - an "act of God". Drink it in, feel it, and then tell me that a good and righteous God is punishing these people for their wickedness.

I don't believe you can. And I don't believe you could praise the God who destroyed Tyre, Sidon or Ashkelon, if you had been there. If you could see in the pages of your Bible what you see on the nightly news, if the genocide and destruction could be real to you, I think you would take a different view of Christianity and it's God. Your Bible stories are the stories of New Orleans, South-East Asia, September 11th, Somalia, Rwanda and the Holocaust, told by those who claim catastrophes as the judgment of an vengeful God. Your Bible is soaked with the blood of the dead and the doomed. You Bible is the chronicle of the conquests of the Lord of Hosts.

I cannot tell you if Katrina is the wrath of the Christian God. But I can tell you that He has orchestrated countless similar disasters. Do not forget this, Christian. Do not ignore it or excuse it or conceal it. You must deal with this fact if you believe your Bible: your God is a god who slaughters nations, destroys cities, and takes vengeance on children for their father's sins. Your God is a god of wrath.

Tell me, Christian, (because I carry this same burden) how do you deal with this knowledge?

[+/-] Jacob Returns |

Hello, I'm back. I've been more or less computerless for the past few weeks. I've had an awesome time doing entirely non-computer related things, but I'm glad to be blogging again.

So I ended up counseling for the final week of the summer, which was totally unexpected. Ever since the camp first contacted me in January, we've agreed that I shouldn't counsel, because we disagreed on some fairly foundational points of doctrine (inerrancy of scripture, damnation for all non-Christians, etc.). But they were in desperate need of another counselor for the final week, and I decided that maybe I could do it after all. To my surprise, they agreed. I'm not very good at guessing God's will, but it seemed like an interesting coincidence to me. If the issue had come up three days earlier, I'm sure I would have never considered asking to counsel. What changed? I'd been thinking the previous few days about what I believe, and this is roughly what I'd come up with:

As a child, I defined my spirituality by my beliefs. A Christian for me was someone who held all of the correct views on matters of theology, ethics, church practice and so on. A couple years ago when my beliefs began to change, it seemed like a terribly significant occurrence. Like anyone whose faith centers on his creed, I was shaken to find that it is possible for honest beliefs to change. Of course, my changes of perspective presented a huge problem when I wanted to work with various organizations whose statements of faith clashed with mine. I thought it was impossible for people to work toward a common goal when they differ in their beliefs about such important issues as women's roles, the importance of baptism, or the chronology of the end times. Just recently I've started to think that maybe all of these issues are secondary. So here's my statement of faith:

I believe in love, first and foremost. By 'love' I mean a change of focus from ourselves to others, selflessness, others-centeredness, compassion, servanthood, self-sacrifice. I believe in the ability of love to transform both the giver and the receiver. I believe that love is the catalyst for joy, for righteous living, and for every good thing. I believe love is the beginning of everything, the reason for everything, the goal of everything. I believe that the purpose behind the universe, the existence of mankind, all of history and every act of God is the creation of a community of love.

I am one who pursues love, first. I am a Christian second, and I am a Christian because what Christianity says about love makes sense to me. I attach little value to Christian beliefs or practices, except to the extent that they nurture or demonstrate love.

I believe that I can work with people whose beliefs and practices differ from my own so long as the goal of their ministry is love, and I believe (though I respect those who disagree) that my identity as a Christian and as one who pursues love qualifies me to work with other Christians.

I wrote recently that I've been thinking of finding a new group of people with which to serve and fellowship - people who believe stuff more similar to what I believe. Now I'm thinking that maybe I can still be a part of the more conservative group I've grown up in, because maybe our unity of focus is more important than our differences of doctrine. We'll see how it all plays out.

I start school in twelve hours. It's good to be back.

[+/-] Three Worship Songs I Hate |

I figured it's time I ranted about Christian worship songs. Some of them I like, of course, but there are others that I loath. In the interest of brevity, I'll mention only the three that are most irksome to me at the moment. I've been trapped in a church service with each of these recently.

I can feel you flowing through me

Holy Spirit come and fill me up

Come and fill me up

Love and mercy fill my senses

I am thirsty for your presence Lord

Come and fill me up

Lord let your mercy wash away

All of my sin

Fill me completely with your love

Once again

I need you

I want you

I love your presence

I need you

I want you

I love your presence

The opening line is enough to condemn this song in my mind, but what really gets me is not the claims of physical sensations of God's presence, but how it flip-flops between "I feel God's presence" and "God please come" lines. How can you follow "I can feel you flowing through me" with "Come and fill me up"? To me, this amounts to admitting that the former sentiments were untrue (or at best, premature), which makes it sound like the whole song is an effort to simultaneously coax God into revealing himself and (in case God is uncooperative) brainwash yourself into believing that you can feel God's presence. At any rate, the whole focus of the song seems to be our desire to experience pleasurable sensations. This isn't worship, it's spiritual drug-abuse. And speaking of brainwashing:

Is it true today that when people pray

Cloudless skies will break

Kings and queens will shake

Yes it's true and I believe it

I'm living for you

Is it true today that when people pray

We'll see dead men rise

And the blind set free

Yes it's true and I believe it

I'm living for you

I'm gonna be a history maker in this land

I'm gonna be a speaker of truth to all mankind

I'm gonna stand, I'm gonna run

Into your arms, into your arms again

Into your arms, into your arms again

Well it's true today that when people stand

With the fire of God, and the truth in hand

We'll see miracles, we'll see angels sing

We'll see broken hearts making history

Yes it's true and I believe it

We're living for you

Is it actually true today that prayer can raise the dead? Is it? THEN WHY ARE WE SINGING ABOUT IT? Maybe I'm making too big a deal out of this. I feel a little like the hyperbole police. It just bugs me that we willingly, passionately, joyously sing stuff that we would find ludicrous if not set to music. It's clear that this song is pure pep, and as such probably should not be taken too seriously, but I don't like seeing people getting comfortable saying whatever the church expects them to say without scrutiny. And finally:

All who are thirsty

All who are weak

Come to the fountain

Dip your heart in the stream of life

Let the pain and the sorrow

Be washed away

In the waves of his mercy

As deep cries out to deep

(we sing)

Come Lord Jesus come

Holy Spirit come

This song drives me crazy. Pain and sorrow cannot be simply "washed away". Not by choice, and not by request. This is the worst kind of lie that Christians tell because it belittles people's pain. It's so condescending, like saying "Just quit clinging to your heartache!" as if people feel pain by choice, as if they need to be coaxed into letting God heal them. "Hey, person in pain, have you considered praying about it? Have you considered asking God to give you life?" Has it occurred to you, song-singer, the damage that this kind of tripe can cause? I can only assume that you've personally experienced the kind of pain-washing you're singing about (and if this is the case, I'm glad for you) and you assume that what worked for you will work for everyone else. Open your eyes.

What really bothers me about worship songs is how you can get a whole church-load of people to sing without blinking something that they would never say to another person, or tolerate from the pulpit. Imagine how people would react if I stood up in church and said "Isn't it wonderful how we all have a physical sensation of God's presence?" or "Bob's Grandma passed away yesterday. Let's all pray that she'll be raised from the dead." or "God will take away all your pain and sorrow right now if you just ask him to." Why do you sing stuff you don't believe? Or do you disagree with my assessments of these songs?

(Slightly off topic, but too good not to link to.)

[+/-] Things I Thought this Week |

This will be random.

I'm reading Soul Survivor by Phillip Yancy. It's good. He talks about some really interesting people, especially Gandhi, about whom I knew very little. Gandhi is my new hero.

It's good that I'm not counseling. In some ways I wish I was, just because pounding nails isn't very stretching, but I know that I couldn't do a lot of the things that would be expected of me as a counselor, not the least of which is singing certain songs. Some Christian music is really awesome, but some of it is disgusting.

I'm reminded that I have far greater control over my emotions than I like to think. Under most circumstances I can dismiss anger, jealousy or infatuation through conscious choice. This is very cool.

Sometimes I think I'm not much more heretical than most of my friends. Often I'll tell someone about my newest divergence from orthodoxy only to see them nod in agreement. I think the biggest difference between me and many of the people who are happily counseling and preaching at camps is that I'm up-front and vocal about my unorthodoxy, and most people just keep their mouths shut.

I have no idea what I'd say to a kid if one were to ask me a about a spiritual issue on which my view diverges from my church's. I don't think it's entirely healthy (or entirely possible) for a young kid to think the way I do. To be blunt and truthful about my beliefs with an 8 year old would be irresponsible. But I'd feel like a liar if I fed them some Church doctrine I completely disbelieve. I like the idea that we're not obligated to always tell "the truth" but rather to say what is beneficial to the hearer at that specific point in time. I suppose the problem is I have no idea what that might be. I guess I'll have to sort that out before I become I father.

The idea of relationship with God amuses me to no end. It used to drive me crazy, but now it mostly seems comical. Imagine having a relationship with a being whose very existence is a matter of debate! (I don't mean that to sound condescending to those who do have such a relationship. I'm not saying you're wrong, I'm just saying the whole thing strikes me as funny.)

Next week I'm doing maintenance again. I'm not particularly looking forward to it, but I'm certainly not dreading it either. It will be good.

And now I am tired. And now I am going to bed.

[+/-] Off to Camp |

I'll be leaving for camp soon. I don't know how much I'll be home over the summer - for the most part just on weekends, if anything. It feels a little strange to be doing no counseling (basically I'll be on maintenance and dishes), a result of being deemed too unorthodox to talk to kids. The camp where I spent the majority of the last two summers doesn't even want me as a chore boy.

I'm not at all angry or resentful about this. It's not that I love counseling so much (in fact I usually find it quite challenging and discouraging) and it's not that I think I'm too good to wash dishes or pound nails, because I often enjoy that kind of work, but I can't shake this feeling that the church views me as some kind of spiritual invalid, with nothing to offer but my body. I don't mean that the Christians I know think of me that way. (Well, maybe they do - how could I know? But they're nice about it.) But I'm feeling more and more like the church has little use for me, or like I don't belong in the church.

At the risk of repeating myself, I have no complaints about my Christian friends, my church leadership, or the people at my camps. Believe me, if I had a problem with them I'd talk to them about it, not whine about them in my blog. My people are great people, but we're different. Our beliefs are different, our mindsets are different, our goals are different. It's not that they won't let me counsel, it's that I couldn't counsel. I couldn't do what would be expected of me. I couldn't say what they want me to say. We're just different.

My church has a communion service every Sunday morning in which anyone can stand up and talk about anything, so long as it's related somehow to Jesus and the whole atonement thing. Sometimes I love this service, because people can be real and share what they're thinking about stuff, but other times I don't understand what people are saying. I'm trying to articulate what kinds of things I don't get, and I think it's basically anything about Christianity having a practical impact on our lives. (Our lives, mind you. I have no problem with someone saying "Becoming a Christian changed my life in this or that way." But I have a hard time with "Isn't it wonderful how we [collectively, as Christians] are different in this or that way!") If there's one thing I've learned about Christianity, it's that it affects people differently.

I suppose the problem with Christianity is that you can only really be a Christian if your beliefs and experiences fall within certain parameters. I guess everything's like that, right? The difference is that Christianity thinks it's for everyone, or to put it another way, it thinks everyone's beliefs and experiences can be defined in it's own particular way. Depending on which Christian circles you move in, you may be able to get "in" to a certain point while still being a quite different, but you'll never totally fit.

It's like hanging around with a group of people who have all known each other for years. They may be great people, they may know how to have a good time, they may be deep and real, they may do a good job of including you and making you feel welcome, and yet they'll always have a deeper connection between each other that you don't have, and you'll always feel like a bit of an outsider with them.

I've gotten fairly good at fitting in. I don't try to hide my differences, but I try not to shove them in people's faces either. I'm used to checking up with whatever ministries I'm in to be sure they're aware of who I am and are ok with me doing what I do. I speak in communion service when I can and I try to keep my mouth shut when I deem my thoughts too radical. I do my best to encourage and help others in their Christian lives even when I can't relate to them. And it hurts me to express discontent with my little Christian world because I dearly love these people and I believe they love me too. My friends are good friends, and I always hate to see any of them go. I'm not sure what I'm saying here. Maybe I don't need to get out of the circles I'm in so much as I need to get into new ones. I want to connect with a broader range of people and find places to serve where my convictions and beliefs aren't a hindrance.

I don't know how I'll do this. I might go searching for a crazy-liberal church or a secular place to volunteer or something like that. Maybe I'll become really outgoing at school and make lots of philosopher friends. Or maybe I'll do nothing.

Anyhow, I think what I meant to say in this post is that I'll be going off to camp tomorrow. I'll be back now and then, mostly on weekends, but I don't know how much blogging and stuff I'll get in. Hopefully I'll be able to do weekly updates like I did last year.

A couple more things:

Now seems like a good time to plug bloglines.com. Sign up (It's easy! It's free!) and they'll notify you each time a blog you read has new content. This has the twofold benefit of saving you the need to check various blogs for new posts and boosting my ego when the subscribers number above my blog goes up.

In the middle of writing this post I came across an article on leavingfundamentalism.org which addresses precisely this topic. If you're interested, here she is.

[+/-] Moving Beyond the Bible |

My Journal is now complete. The final two months of July and August are now up.

So in Buddhism there's this idea that not everything the Buddha taught was "true". Rather, he taught what was expedient, or useful and relevant to his audience. I really think they're on to something. Applying this to the Bible, it's easy to see why God didn't give the Israelites at Mt Sinai the same moral guidelines he gave through Jesus later on, or that he convicts various people of today. You can't just walk in to a culture and say, "Everything about the way you're thinking and acting is wrong. We need to tear this down and rebuild everything from scratch, and it's going to look like nothing you've ever seen." People just can't handle that. So it's baby steps: baby steps to treating women humanely, baby steps to seeing women as equals before God, baby steps to treating women as equals in society.

Most Christians are quite willing to admit that not all the laws given to ancient Israel are still applicable or sufficient. In fact, most of us would be appalled by the barbarism of a society like the one crafted by God himself (as some of us believe) all those years ago. And I'm not talking about the pagan, lawless society that Israel so quickly and repeatedly became - I mean a hypothetical Jewish society based entirely on the laws given to Moses. These laws simply wouldn't work in modern western society. They were beneficial for the time and place, but we've moved past that now.

I can see you all nodding in agreement. But now let me suggest that maybe we've also moved beyond the New Testament's teachings in some areas too. You don't like that? Why? It can't be that the laws given by Jesus are more authoritative - not if the Jewish laws were put in place by the Father. By all accounts, the transcendent God who created the Jewish laws is just as Holy and omniscient as the Son of Man who preaches in the Gospels. So why do we view the Father's laws as transient and the Son's as permanent? Because the Son was the final revelation of God? That makes sense. If there have only been two revelations of God (and his laws) to humanity, it makes sense that our religious and moral lives be defined and contained by the second. But what about that other person of God? You know... the Holy Spirit? (Can you see where I'm going with this?)

Ok, I admit I'm the first to downplay and discount the Holy Spirit and his supposed work in my life. I'm one of those who trusts my own experience and common sense over the Bible, and doing so in this case means that I have very little interest in the Spirit. But supposing I took every word of the Bible to be true, (though of course not your interpretation of every word) I think it still makes hella sense for the Bible not to be the be-all and end-all of Divine revelation. If the revelation of the Law from the Father is trumped by the later revelation of grace from the Son, shouldn't it follow that the present revelation from the Spirit through our consciences trumps the stuff in the Bible? Why should we feel bound to live entirely according to Biblical teachings, especially when the Bible gives little indication of being intended as a divine rule book? Why should we feel obligated to give chapter-and-verse support for every moral conviction we espouse? (Isn't this dishonest - pretending to be building all our morals on the foundation scripture when in reality we're forcing scripture to fit our inherent ethical convictions?) If you really believe that you are indwelt and empowered by God himself, why is your inner voice subservient to the written records of past revelations? Sure, there should be some kind of consistency, but we shouldn't be afraid to own up to the kind of divinely influenced yet culture-specific morality that was pioneered explicitly by God with the "New Covenant".

You want a precedent for the Spirit inspiring shifts in Christian moral thinking? How about the Epistles? Even within a generation of Jesus' death, even when Christians had access through the Apostles to all his teachings (not just the ones found in the canonical gospels), this revelation was insufficient to address all moral and spiritual questions. (No slight to Jesus, it's just that he didn't personally give orders for every possible scenario. How could he? Why would he?) The Apostles, guided by the spirit, took it upon themselves to both interpret the teachings of Christ and add to them, where necessary. They did this for their culture and their issues, so why should we hesitate to do it for ours?

I'm not suggesting that we throw out the Bible, any more than the early Church threw out the law of Moses. But let's see it for what it is: books written by men (guided by God) to address the issues of their day, just as we (guided by God) address ours. Let's see it as a reference point, as guidelines, but not as a holy rule-book that transcends all cultures and covers every issue, nor as the final word on any matter. I'm not suggesting we throw caution to the wind and chase after every hedonistic or idealistic whim, but lets stop seeing God as a stodgy old man who grumps about anything that's changed in the past 2000 years. I love the Bible. The Bible is good. But it shouldn't be the final word.

[+/-] My New Focus |

I'm not that interested in God anymore. I remember when I used to think about him all the time. I haven't really done that in months. I no longer think of God as a person most of the time. Now he's kind of a concept. A hypothesis. I have no real interest in "relating to" God. There's nothing about the dynamic between God and myself that resembles a relationship. We don't talk. (Well, I talk sometimes, but we don't converse.) We don't really interact in any way. I've come to the point where I feel like I believe in God, but that it's not a belief that I attach a lot of significance to. (When I talk about whether God exists, I mean whether he exists as a being who influences our world and is involved in our lives. I have no interest in a transcendent "first cause" type being - only in a being that has some relevance to my world.) I am of the opinion that God exists, but I don't think it would affect my life in any huge way if I changed my mind.

I was thinking the other day about why I'm a Christian. I think it's probably mostly because the people around me are Christians. It is convenient for me to believe certain things because it allows me to relate more closely with those around me. I'm not saying I don't believe in Jesus and all that stuff - I do - but I believe out of conscious choice, and I choose to believe because it's expedient, and also to a certain extent out of inertia. (I've always been a Christian, there seems to be nothing better out there, so why change?) I'm also not saying that there are no good reasons to be a Christian, or that I suspect the whole thing is untrue. I'm just saying that I don't care so much whether it's true. Well, I suppose I still do care. But I don't expect to ever come to a firm conclusion, and it's no longer my greatest concern.