Hi.

Sorry about my much-longer-than-expected absence. I've been (and continue to be) busy and distracted and a little bit writers blocked. There probably won't be much here until Januaryish.

I do have things to say, but I'm having trouble getting them down in writing. This happens to me sometimes.

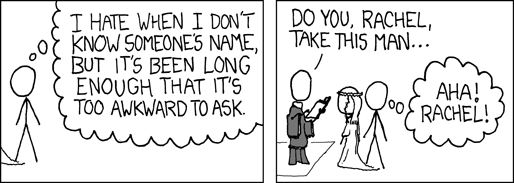

In the mean time, here's another gem from xkcd:

[+/-] Happy Holidays |

[+/-] Stuff |

I'm sorry for the lack of posts recently. I'm midway through my end-of-term essay writing frenzy. By this time next week I will be free.

Until then, here's some stuff:

Apparently this blog reads at an undergrad level.

I'm more than a little skeptical. Not sure what the creator was reading in college, but it clearly wasn't Kierkegaard.

I'd like to think that the average high schooler could make sense of my writing, but I guess I do use big words sometimes.

Here's a shocker: apparently this blog is worthy of a NC-17 rating. Why? Primarily my liberal use of the words "pain" and "hell". Riiiight.

Good thing the kiddies can't read it anyways.

And have you ever wondered where I fit in the wide world of Christian theology? Wonder no more!

What's your theological worldview?

You scored as a Emergent/Postmodern

You are Emergent/Postmodern in your theology. You feel alienated from older forms of church, you don't think they connect to modern culture very well. No one knows the whole truth about God, and we have much to learn from each other, and so learning takes place in dialogue. Evangelism should take place in relationships rather than through crusades and altar-calls. People are interested in spirituality and want to ask questions, so the church should help them to do this.

Emergent/Postmodern

89%

Modern Liberal

64%

Classical Liberal

61%

Neo orthodox

54%

Evangelical Holiness/Wesleyan

43%

Roman Catholic

32%

Charismatic/Pentecostal

25%

Reformed Evangelical

14%

Fundamentalist

0%

That sounds about right. I confess I don't know much about Neo Orthodoxy, Evangelical Holiness/Wesleyanism, or the differences between Modern and Classical Liberalism. (Anyone care to enlighten me?) But I do like what I've heard about the Emergent church (primarily via Brian McLaren), and the blurb at the top sounds pretty good to me.

Want to see your theology expressed as a bar graph? Of course you do! Take the quiz here.

And a few links for good measure:

Here's the most interesting thing I've seen this week (via slacktivist).

Jim at Straight, Not Narrow weighs in on the "War on Christmas".

My current favorite web comic is xkcd.

[+/-] Real Live Preacher |

Note (July 08): I've updated the links in this post - most of these stories are now in the rlp archives. Just so you know. Also, at this point the Preacher is no longer shipping his books, which is a shame. I trust he'll start again at some point. I recently read RealLivePreacher.com (the book), by Gordon Atkinson. I finally bought a copy because the Preacher is now selling them personally (there's a story behind that, if you're interested). Each book now comes with a little handwritten note and a couple random objects stuck between the pages.

I recently read RealLivePreacher.com (the book), by Gordon Atkinson. I finally bought a copy because the Preacher is now selling them personally (there's a story behind that, if you're interested). Each book now comes with a little handwritten note and a couple random objects stuck between the pages.

Nearly all the essays in the book can also be read on his blog, but for some reason it's exciting to have them in tactile form. And as a bonus, I now have a slightly risque free beer token from some pub in Texas, a CD of Mexican music, and a packet of vanilla chai tea.

The book is worth buying, even if you're not an avid reader of the blog. It's kind of a "best of", and it makes a good introduction to the Preacher. Most of my very favorites are there, such as:

The Preacher's Story

George the Middle, Beginning and End

The two about Rabbi Jonah and Robert

The Advent and Passion of Elliot

John the Baptist (still cracks me up)

Bifocals

These are excellent stories. I don't like to throw around the words "must read", but I'm tempted to invoke them here.

And if you want to read more, here are a few good ones that didn't make the book:

The Truth About Snow

The Soft Stories series - Old Man Cedar, Chloe, Looking For Elliot and Main's Folly

The Gospel According To Anna

The Foy Davis series

The Preacher also wrote an excellent dramatic version of the Christmas Story, which is now available as an audiobook. It's beautiful and insightful, and well worth purchasing.

[+/-] I Want To Pray To Mary |

Hail Mary, full of grace.

The Lord is with you.

Blessed are you among women,

and blessed is the fruit of your womb.

Holy Mary, Mother of God,

pray for us sinners,

now and at the hour of our death.

It's such a beautiful prayer. So poetic. Reverent, but warm. Grace, blessing, holiness, a plea for intercession, and an acknowledgment of mortality. You could not write a better prayer.

The problem is I don't believe that Mary stuff. I don't believe she has some special power or authority, and I can't help but feel that God doesn't approve of me praying to a dead woman. Particularly because I don't believe in it. I don't have a problem with those pray and believe it, but I feel like I shouldn't, because I don't.

I say the prayer and the words are hot in my mouth. They taste like swear-words tasted in grade two, like beauty tinged with blasphemy.

Will God forgive me this prayer? I don't pray much. Will God appreciate the reverence of this prayer, how it makes me aware of my need for grace and help, and the feeling of comfort and security it brings me? Or is He angry that I long to pray to a mortal, but have so little to say to Him?

I firmly believe that it doesn't matter what name we give to God. He's called a thousand names; I think He can figure out who we mean. And I don't think He minds that most of us pray to a well groomed, Caucasian Jesus. But "Mary" is not a name I have for God.

Even "Mother" doesn't bother me. Nothing wrong with a Mother God, whatever Johnny Cash says. (That line about the father hen really pisses me off.) But Mother of God is something else.

Maybe I can't do it. That makes me sad.

But I can certainly say "La Elaha Ela Allah". It doesn't have quite the same feel to it, but it's beautiful and meaningful, and I think I really believe it.

La Elaha Ela Allah.

There is no god but God. So I probably shouldn't pray to Her mother.

[+/-] On Pain and Its Redemption |

I got thinking recently about the idea that all the suffering we experience is ultimately for our own good. It's true that we often seem to become stronger, wiser, more compassionate, and so on, as a result of hardship. Perhaps God is justified in allowing or causing pain because ultimately the good it produces in us outweighs the inherent evil of our suffering.

For most of us (Kantians may disagree), the ethicality of inflicting pain on someone "for their own good" is a question of ratios. How much pain are we talking about? How much good may result? How likely is the desired result, how devastating the worst case scenario, etc. I think we can agree that disciplining children, in a reasonable and restrained way, is necessary and good. Few of us would wish that we had never experienced pain, and perhaps some of us who have experienced great pain believe that it ultimately worked for our benefit or betterment. It's difficult to speculate about what a completely pain-free creation might look like, but I'm willing to concede that a certain amount of pain (perhaps much more than I would think) is necessary in order to make us what we are meant to be.

Still, it's hard to imagine all the pain we experience having a positive effect. I don't have a problem with God putting us through adversity, but sometimes it feels like He's pruning with a canon. Pain seems to weaken or destroy people as often as it heals them.

It's not the existence of pain that bothers me. It's not even the amount, strictly. (It certainly looks excessive to me, but who am I to say what's necessary?) What horrifies me about pain is that it seems to be distributed completely at random. Pain falls in great mounds and bare spots, choking many of us with more than we can bear and leaving some with less than they need. Could it be that the God who wrote the laws of physics and wove our DNA allows suffering to rain down on us, but cannot regulate the flow? Or am I to believe that tsunamis and genocides are doled out with eyedropper precision? How then can I account for those who are overwhelmed and ruined by extraordinary pain?

In my attempts to account for what seems to be a profligacy of suffering, I feel that I have a choice between two extremes: either I must believe that God is in way over his head, powerless to reign in the horrific and gratuitous suffering of so many of his creatures, or else I must believe that God's power far surpasses even my wildest dreams.

Please do not confuse the latter god with that of orthodox Christianity. I'm talking about a god who possesses power and a plan that far surpasses what any religion permits me to hope for. A god who is at work on something wholly beyond my understanding - a god who will not merely bring an end to suffering, but who secretly collects every drop of senseless pain and evil and works it all for some greater good.

I don't see a place for a middle-strength god - one who commands the wind and the waves but cannot stop hurricanes and tsunamis, who saves forever His elect, but loses the rest of creation to hellfire.

I don't think the profusion of senseless and destructive suffering is a mere misperception. I see evil in this world that no theodicy can account for, and no god I've heard of could possibly set right. I do not have the ability to be optimistic about the ultimate goodness of our suffering. My only choices are dark pessimism, or wild, desperate hope.

[+/-] What I Learned About Quakers |

I attended a Quaker church last Sunday. He's what I think of when I think Quakers:

1. Underground railroad

2. Old-fashioned clothes, like the the oatmeal guy.

3. Pacifism

4. Mysticism

Pretty good list. I've always thought Quakers were awesome, even though I didn't know much about them.

Well it turns out Quaker meetings are boring as hell. Seriously, this may have been the most boring church service I have ever attended in my life. But not in a bad way. I mean, I can imagine it being good if I was a different person. Basically it was 45 minutes of silence, followed by a brief open sharing time. People just talked about what they'd been thinking about; none of it was overtly "spiritual".

So I'm not likely to attend their meetings on a regular basis, but I am pretty much in love with them. Specifically their beliefs and values. Their big thing is that each of us individually is guided by God, and that this guidance, not the Bible, is our ultimate authority. They don't believe in creeds, religious hierarchies, or church rituals. Sometimes I wonder if Christians really believe we're indwelt by the Holy Spirit, and what we might look like if we did. Maybe we'd look like the Quakers.

So they're radically individualistic, and also really into experiencing God, in a low key, mystical kind of way, but they're also big on community. That's why they come together to sit quietly for an hour: apparently they're actually seeking some kind of communal mystical experience with God. They get awesome points for putting the words "communal" and "mystical" in the same sentence.

They're so serious about this that they make decisions by consensus. They have no church leadership of any kind. Instead they have business meetings were they each listen to what they feel is God's leading and then they talk about it until the all agree.

Also, they're extremely egalitarian, and have been since the beginning. Not only did they oppose slavery, but since their conception in the 17th century Quakers have refused to acknowledge class distinctions and have treated women as social and spiritual equals. (Who would have guessed the Quaker Oats guy was a feminist?)

Other cool things: they dress plainly, they've never been anti-intellectual, they don't distinguish between the sacred and the secular, they don't believe in telling lies or attempting to deceive in any way, they'd sooner go to jail than fight in a war, and they welcome non-Christians as full members of their communities. You can be a Muslim, a Buddhist, or an Atheist and also be a Quaker.

(Apparently there's a more conservative branch of Quakers which places more emphasis on the Bible and conducts slightly more conventional meetings. The statements above are generalities, and are probably more accurate for liberal Quakers.)

I know not all of you will be as impressed by this stuff as I am, but whatever you think about their beliefs (or however boring you find their meetings) you have to respect these people for the way they live their convictions. Besides the anti-slavery stuff, Quakers won the 1947 Nobel Peace Prize, and have been involved in the founding of organizations like Greenpeace, Oxfam, and Amnesty International.

[+/-] Ebenezer Scrooooge |

I attended the St Joseph's College Chapel this week. I liked it. It still had that high church feel, but was small enough to feel cozy. They read the story of the rich man and Lazarus, which I found confusing. Here's the last bit:

"Then I beg you, father, send Lazarus to my father's house, for I have five brothers. Let him warn them, so that they will not also come to this place of torment."I find that hard to believe. Does Jesus really think that people who don't listen to scripture won't be moved by miracles? Don't we all know people who repented only after experiencing a miracle? And didn't miracles accompanied the words of God throughout the scriptures, particularly in the cases of "Moses and the Prophets"?

Abraham replied, "They have Moses and the Prophets; let them listen to them."

"No, father Abraham," he said, "but if someone from the dead goes to them, they will repent."

He said to him, "If they do not listen to Moses and the Prophets, they will not be convinced even if someone rises from the dead."- Luke 16:27-31

Didn't God preform many miracles through Moses to give authority to his message?

Didn't Elijah, the greatest of the prophets, call down fire from heaven to prove to Israel that his God was the true God?

Didn't Jesus give his witnesses miraculous power, and wasn't the performance of miracles a cornerstone of evangelism in the early church? Wasn't the great missionary Paul converted as the direct result of a miracle (specifically, an encounter with a dead man)?

Didn't Jesus himself augment his teaching with miracles? Didn't he use these miracles to shock people, to make them think, and to establish his authority as a messenger from God?

And isn't Jesus' own resurrection from the dead the cornerstone of Christianity? Didn't this great miracle (the very thing that the parable says would change no one's mind) open the disciples' eyes to the truth of Jesus' message?

This parable's perspective on miracles sounds very modern to me. People are always trying to tell me that we don't get a lot of miracles these days because people wouldn't listen to them anyway, and the Bible by itself should be enough to convince anyone. I don't see that anywhere in the Bible ...except here. Can anyone explain this to me? Can this passage be harmonized with the flashy methods of prophecy and evangelism that pervade the Bible? (I've included a few biblical counterpoints below.) Does anyone believe that people who reject the Bible would not be moved even by an encounter with a dead man?

I will not venture to speak of anything except what Christ has accomplished through me in leading the Gentiles to obey God by what I have said and done— by the power of signs and miracles, through the power of the Spirit.- Ro 15:18-19

But I will come to you very soon, if the Lord is willing, and then I will find out not only how these arrogant people are talking, but what power they have. For the kingdom of God is not a matter of talk but of power.- 1 Cor 4:19-20

And if Christ has not been raised, our preaching is useless and so is your faith.- 1 Cor 15:14

[+/-] Hell and Justice |

I've been rethinking hell. It's been along time since I took seriously the idea that humanity deserves eternal suffering. But I decided I should try to make a cool-headed assessment of the various possibilities. I’ve approached this by considering what might constitute a just cause for damnation.

1. Anything at all, or even nothing

This is the view that God needs no reason for causing his creatures infinite suffering. Rather than God being just because He acts justly, His actions are just because they're performed by God. God alone makes the rules; there are no transcendent moral laws by which He abides. The interesting and troubling implication of this view is that there is nothing inherently wrong about any action, however horrific it may seem to us. So the only reason why rape is wrong is that God says "Don't rape people". If God didn't command us not to rape, there would be nothing wrong with rape.

So is justice a transcendent law, or merely a part of creation? I suspect that most of us can imagine something an almighty God would be capable of doing which would be wrong. (He may in fact be prevented from doing it by His inherently just nature, but that's another issue.) I think causing immeasurable suffering to a helpless and undeserving creature is an example of something that would be unjust even for God. Consequently, if we are to believe in damnation, we must believe that it is something we deserve.

But you could take the opposite position - that anything God could possibly do or command would be just. My problem with this, besides the effect it has on my stomach, is that this makes justice kind of an empty concept. How can we make sense of saying "God is just" if "just" simply means "what God is"? If all God’s qualities are understood this way, it’s difficult to understand why He’s worthy of worship or obedience or love.

2. Someone else's sin

So if I've established that God is in some way constrained to act justly, the next question is whether (or to what extent) I understand what justice is. Is it possible that my own intuitions about justice could be wildly mistaken, and that justice permits - or even requires - one person to be punished for the sins of another? I'm don't think I could imagine anything that seems more fundamentally unjust, but it appears that at least some biblical authors disagree. Could it be that every one of us is guilty and deserving of damnation because of our ancestors' sins? That even infants who do not have free will and thus have never sinned are nonetheless under the righteous wrath of God? I have a hard time believing that my moral intuitions - intuitions which I'm told are given to me by God, those same gut feelings that tells me rape and murder are wrong - are so drastically mistaken on this point. The idea that we are justly found guilty of crimes we have not committed is beyond my imagination.

If this is justice, am I meant to comprehend it? Might I some day understand rationally that children are guilty of their parents' sins, and that every one of us really deserves to burn for Adam's disobedience? Or is it something that I must take on faith? If I were to try to believe that what seems to me the most grievous of all possible injustices is, in some unfathomable way, completely just, I would have to have to have enormous confidence in the source of this doctrine, and in my correct understanding of it. I'm a long way away.

3. One's own sin

If we accept that God acts justly, and that our understanding of justice is not wholly mistaken, we can move on to the question of eternal punishment. I fully understand that I am an imperfect creature, both by nature (which is not my doing, and for which I am not deserving of punishment) and continual choice (for which I do deserve punishment). I recognize that I do not deserve to stand before a holy God because of my willful unholiness. But do I deserve infinite punishment for my finite sin? If I've decided to believe that there is such a thing as justice apart from the will or whims of God, and that it is at least somewhat comprehensible to me, can I make sense of the idea that unending torment is a fitting punishment for finite sins?

The first thing we have to get out of the way is the idea that some people deserve eternal torment and others don't. If there were any relationship between the degree of sin and the degree of punishment, no one could possibly deserve infinite punishment. As creatures with finite wills and powers, living finite lives in finite worlds, we cannot do infinite evil. So either Hitler does not deserve eternal suffering, or you and I and Mother Teresa all deserve it as well. If we believe in eternal punishment we must sever the intuitive link between the severity of a crime and the severity of its punishment.

Which is a hell of a task. Even ignoring the mind-boggling prospect of infinite suffering, can we accept that all crimes are deserving of equal punishment? Can we accept that a lie is precisely as damning as an act of genocide? I can't see how.

Once again, we cannot say that we're so evil we deserve eternal punishment. Either we deserve it because we are less than absolutely perfect, or we do not deserve it. Is eternal torment just punishment for the smallest imaginable sin? Again, I can't see how.

My conclusion at this point is I don’t believe a just God would punish anyone with eternal suffering. This is not the same as believing there is no hell. I've by no means considered all possibilities here, but it's a start. I may consider other options in a subsequent post. Anyway, let me know if you disagree on any point.

[+/-] Church Hopping |

I'm still here. I'm just kind of busy. I have a big messy post in the works and I'm having a hard time finding the time and energy to finish it. Also, I haven't got around to looking into the non-Christian YECs a recent commenter suggested. I'll let you know what I think when I get to them, either in the comments or a new post.

Just thought I'd let you all know about one of my projects for the immediate future. I've decided to stop going to my regular church, at least for a while, and check out a wide variety of other local churches. My main goal is to get a taste of many different ways of doing church (sort of a Generous Orthodoxy thing) and develop a basic familiarity with different denominations. And if I find a church where I feel like I fit in really well, that would be cool too.

I went to St Joseph's Basilica this week. I don't think I'm really a high church guy, but it's nice for a change. It's weird to think about how much money a building like that costs. I don't know whether an expense like that can be justified, even though it's really pretty. I have a hard time imagining Jesus of Nazareth approving of a building like that. On the other hand, he approved of spending a year's wages on perfume for his feet, and God himself ordered the construction of Solomon's temple. I don't know. Anyway, if anyone knows of an interesting, unique or awesome church in the Edmonton area, I'm open to suggestions.

Since I'm doing personal updates, my Bible-writing project has stalled. I've made it to about Matthew 15, but I haven't picked it up in a while. I still intend to.

[+/-] The Problem With YEC |

I try to stay away from debates about the age of the earth or the methods by which God created life. For one thing I haven't done nearly enough research to have an educated opinion on the matter (although that doesn't stop a lot of people). For another, I don't particularly care.

I do recognize that for many people this is a serious issue. If the first two chapters of Genesis are not literal, historical truth, doubt is cast on the literal, historical truth of all other Bible stories. This is a valid concern, and I do care about how people interpret scripture, but I'd rather talk about that directly than get bogged down in some endless and tangential discussion of flood geology.

I'm not sure if anything could persuade me to take a real interest in Young Earth Creationism (YEC), but I would like to know whether I should regard it as anything more than fundamentalist dogma. I'm quite willing to give the theory any respect it may be due.

There are a couple of concerns that prevent me from taking YEC seriously. One is that I've observed what seems to be a widespread misunderstanding among it's proponents of words like "bias" and "presupposition", about which I have some knowledge, if not expertise. Having encountered what I believe to be incompetence among leading YECists in an area I know, I have difficulty giving them the benefit of the doubt in areas I do not. (I could say more about this, if you wish, but I won't go into it here and now.)

The second thing that prevents me from taking YEC seriously is that, as far as I know, conservative Christians are the only ones who believe any of it.

I stress the "as far as I know". I haven't actually searched for expert, non-Christian evolution or old earth skeptics. I sort of assume that if there were such people they would have been brought to my attention, but it's quite possible (what with me not really caring) that I may have missed them.

So how about it, YECs? Can anyone find a single person who fits the following description?

1. Is a recognized expert in a relevant field (eg. geology). Meaning he or she has a PhD in that field from a respected secular university, and is or was, if not at the top of his/her field, at least well respected by his/her peers.

2. Was not a YEC from the start. Meaning s/he was not raised as a conservative Christian and, without having examined it in detail, had always considered YEC to be mere religious dogma masquerading as science.

3. Now agrees with YEC about what the physical evidence indicates. Meaning that in the course of his/her research, this expert became convinced that the weight of evidence is against some well accepted cornerstone of atheistic evolution and now holds a position very like that of YECs. (Such as that there is strong evidence in the fossil record of a recent, global flood.)

4. Came to this belief on the basis of the physical evidence alone. Meaning that s/he did not convert to conservative Christianity and then change his/her mind about the evidence, but changed his/her mind before and independent of any religious conversion. It would be best if the expert was not a Christian at all.

If the YECists cannot produce such a person (and I don't know if they can or not, which is why I ask) I see no reason to take their position seriously.

[+/-] Camp is Good |

This last week was really good, on the whole. I was a counselor, but with senior campers this time, which is way easier and more fun. My campers were really cool, and I was more at ease than I've ever been as a counselor before. I screwed up a few things, but I was satisfied with my effort.

I really like it here. I'm becoming more aware of the centrality of community to Christianity (that is, being a disciple of Jesus). And I love community, and it's good for me. Often when I'm at camp I have a hard time remembering what my problem with Christianity is. Maybe if it could be like this all the time, I could really start to believe stuff (whatever "believe" means). Maybe my non-relationship with God wouldn't be much of a barrier. Or maybe even that would change.

I feel wistful.

I don't think a whole lot about my post-student life (I graduate this year), but sometimes it gets me really excited. I don't have a clue what I'm going to do next, but I think it could be awesome. I'm young and I currently have no desire to get married; my options are endless. I'll hopefully travel, as soon as I have some money and a place to go and maybe someone to go with. I could get a job that doesn't pay much but brings me joy. I could join a monastery. I could sell everything I have and give it to the poor. I could literally do that.

That's all I've got for now. Counseling is not very conducive to thinking about stuff. But I probably think too much anyway. (Too much or not enough? I'm never sure.) Maybe I'll write you something profound in a day or two.

[+/-] I Choose Love |

I didn't spend a lot of time on the discipleship thing this week. I was on maintenance, which is way more work than chore boying, because there's always another job that can be done. Harry Potter took up all my free time. This next week, by the way, I'll be counseling a teen camp. Prayers are appreciated.

So here's something that struck me recently. For some reason I got thinking about an episode of Adventures in Odyssey (a childrens' audio drama by Focus on the Family, which I listened to constantly as a kid). There's this one where a young guy's about to make the very great mistake of marrying a non-Christian, and the gravity of the situation is driven home by the sad story of his wise and elderly friend, who, it is revealed, had a non-Christian wife in his youth.

I think I'd always been told that Christians shouldn't marry non-Christians because their differing beliefs will be a barrier to intimacy and unity, strain the relationship, and cause disagreements about how the kids should be raised. Intriguingly, none of these concerns were addressed by the Odyssey episode. Instead, it emphasized the intense pain that Jack experienced on behalf of his dearly loved, deceased, and (as far as he knew) unsaved wife, who in all probability was already burning in hell.

It struck me that the implicit message here is, don't love non-Christians too much. Don't care too much about them. Don't feel for them too much of what God feels. Don't understand too deeply their immeasurable, inherent value, because if you do, and they die unsaved, you will see too clearly the incomparable tragedy and horror of hell, and it will break you.

This brings to light a very serious problem with (a certain kind of) Christianity: it both demands that we believe the majority of humanity will suffer eternally, and exhorts us to love others to the greatest degree of which we are capable. If we do both these things well, we are setting ourselves up for unparalleled and (I suspect) utterly crippling, destructive sorrow.

Immediately I can see two (and only two) solutions to this problem. Either we must refuse to believe in hell, or we must moderate our love. I choose not to believe in hell. (This is a more popular solution than you might think - many Christians claim to believe in hell but in reality do not, because they do not permit themselves to think about what they "believe", or allow it to affect their actions.) Focus on the Family (implicitly) recommends the other solution - that we not allow ourselves to care too deeply for those whom we believe will suffer eternally.

I choose to love, therefore I cannot believe in hell. I don't mean to say that I love greatly - if you are underwhelmed with my love, I assure you I am as well - but I love enough that I recoil from the idea of hell. I cannot accept it. Others may have stronger hearts, which can love more deeply before hell crushes them, but I don't believe any heart could survive loving to its utmost ability and believing in hell.

You can call me weak, or cowardly, or naive. I suppose I'm all of those things. But whatever my failings I want, more than anything, to love. I will pursue this zealously. And if my religion hinders me, I know what must be done. I will not be moderate. I will not make compromises.

I choose love, and for this I will not apologize.

[+/-] The Cost of Discipleship |

I'm trying to decide whether I can be a disciple of Jesus (that is to say, a Christian). I don't think I agree with him about everything. Can I be a real disciple and think he got a few things wrong? (I don't like the idea of Jesus being fallible, but if I'm honest with myself, I guess that's what I believe.)

Which things do I think he got wrong, you say? I couldn't tell you off the top of my head. But I plan to look through the all the red text in my Bible this week and see if there's anything I really can't agree with. If I can pry myself away from Harry Potter.

I've been reading The Cost Of Discipleship. Bonhoeffer says that you can't have faith without obedience, nor obedience without faith. There's a brand of Christianity, which seems particularly popular in camp ministries, that emphasizes "faith" at the expense of obedience (this is what James denounces). Conversely, I'd rather practice obedience without faith. I would be content just to be obedient to Jesus (or just to try to be) but maybe obedience sans faith isn't true obedience. (Because faith makes obedience possible, or because believing is part of obeying?) So I'm trying to figure out whether I agree with Bonhoeffer, and if so, whether I'm capable of true obedience, or just a faithless facsimile.

Bonhoeffer complicates things by saying that we cannot choose to be disciples out of the blue; we must be called. I don't know what he means by "called" (it sounds very Kierkegaardian*) but it seems that (as with all spiritual experiences I'm supposed to have had) either I've failed to recognize God's call to me (how? and what do I do to correct this?) or I've not been called at all. Or maybe my conviction that I ought to pursue a life of servanthood and selflessness constitutes the call, but then why would Bonhoeffer make a big deal about the impossibility of obedience without a calling? Who tries to be a disciple without this conviction? I don't know. Anyone understand Bonhoeffer?

*Kierkegaard says that we each choose one of three life-governing principles: desire, reason, or faith. But the last is only open to those who have been called by God to do something crazy, like Abraham sacrificing Isaac. If you want to choose faith but you haven't been called, you're basically hooped. Similarly, Bonhoeffer seems to be saying that you can't possibly be a disciple of Christ if he hasn't called you (because of our sinfulness and inadequacy) although what the call looks like and how prevalent it is is unclear.

[+/-] Just Briefly |

We know that the law is spiritual; but I am unspiritual, sold as a slave to sin. I do not understand what I do. For what I want to do I do not do, but what I hate I do.

I have the desire to do what is good, but I cannot carry it out. For what I do is not the good I want to do; no, the evil I do not want to do—this I keep on doing.

So I find this law at work: When I want to do good, evil is right there with me.

What a wretched man I am! Who will rescue me from this body of death?

In other news, this last week was kind of difficult. The work was good, I enjoyed myself, but I felt very much at odds with the other staff. The speaker said a lot of things I thought he shouldn't have, and it made me wonder what I was doing there. Why do I invest so much of my time and energy in things I don't really believe in?

That's all I have for you.

[+/-] It Really Does Say That |

If, in casual conversation with a certain sort of Christian, you said something like, "I think a person is justified by what he does, and not by faith alone", you might be called a heretic.

If you said, "I think the Bible says a person is justified by what he does, and not by faith alone", you might encounter surprise, incredulity, and even annoyance.

And if you said, "James 2:24 says 'a person is justified by what he does, and not by faith alone'", you might be treated to a long and nuanced hermeneutical discourse, to the effect that the passage does not in fact say anything like what it appears to say.

But if you suggested to that same person that passages dealing with homosexuality, or women's roles, or the origin of humanity don't say what they appear to say, you might be accused of twisting the Word of God to fit your own agenda. This strikes me as inconsistant.

[+/-] What Bugged Me About Junior Camp |

First of all, thank you to all who though of me, prayed for me, or left me encouragements or advice over the past week. The camp went relatively well, I thought. At least, I was satisfied with the effort I turned in.

The thing about junior campers (and my cabin was the most junior of all) is that they tend to be both incapable and uninterested in discussing spiritual matters in any great depth. It's a little bit discouraging to put so much energy into a week with no discernible results, but the whole thing went about as well as I could have hoped.

The one thing that I found difficult that week was talking to kids about "the Gospel" - a concept with which I've become so disenchanted that I have difficulty speaking of it without the aid of quote marks. On the one hand, I think that making a one-time decision to identify with Christianity, to ask God to forgive all your sins, and so forth, can be a meaningful - perhaps even life-altering - experience. But on the other hand, I think it's a little dishonest for me to encourage a nine-year-old to make this ostensibly eternal decision merely in the hopes that it will be "a positive experience for them". For that matter, I'm not sure how I feel about anyone prodding kids this age to "accept" Jesus. If I really wanted to, I could make most of them accept just about anything. Who are we trying to kid?

I feel a lot better about evangelizing senior campers, because they're somewhat more capable of making an rational decision. Curiously, it seems that the pray-to-accept-Jesus bit gets a lot more play at junior camps than senior camps. I wonder why that is. I hope it's not just because they're easy targets.

It wasn't a bad week, on the whole. But I don't think I'll be counseling another junior camp any time soon.

[+/-] My Predicament |

I'll soon be a camp counselor again. That still feels weird. I'd sort of gotten used to the idea of never counseling again, or at least, not counseling any time soon. But somebody wanted me, so I decided to give it another shot. Counseling is something I do because it's challenging, not because I'm very good at it or particularly enjoy it. It tends to put me in curious spiritual predicaments.

There are times when I'm at camp that I feel very Christian. At times faith (or credulity) comes easier to me there, surrounded by dedicated, godly people, and doing overtly spiritual work. There are times at camp when it seems very reasonable to me that prayer would powerfully affect the physical world. There are times when God seems near - if not emotionally, then at least intellectually - and I wonder if I'm silly to be so skeptical during the other ten months.

But at other times (particularly when I'm counseling) camp is where I feel most strongly that there is no God. When I'm at the end of the rope, when I'm fed up and tired and don't know what to do, it's really difficult for me to believe that praying or trusting will somehow make the situation better. God never seems more distant than the times when I need him most.

This puts me in a bit of a predicament. I really believe that if I can keep my focus and maintain a positive attitude, I can be a good counselor. I believe that I sink or swim on the basis of my skill, my strength and dedication. But then I think, if I make this all about me and my abilities, then what the hell am I doing here? This is a ministry. It's about facilitating a connection between my kids and God (although I'm not sure what exactly that means, or if I've experienced it myself) and if I'm not relying on him to guide me and empower me, I'm probably just wasting everyone's time. And yet I can't help but believe that my success as a counselor (or anything else) is a result of my ability and preparation, and that no amount of prayer or trust can save me.

This worries me. A good counselor - an able counselor - shouldn't think this way. How did I get into this? The answer, I suppose is that the camp needed me, and trusted me (trusted my ability, I suppose), and I trusted their discernment. Maybe one of us trusted too much.

If any of you lacks wisdom, he should ask God, who gives generously to all without finding fault, and it will be given to him. But when he asks, he must believe and not doubt, because he who doubts is like a wave of the sea, blown and tossed by the wind. That man should not think he will receive anything from the Lord; he is a double-minded man, unstable in all he does.Where does that leave me? I want to do this right, but I can't make myself believe. Maybe I'm over-thinking this. I am what I am; all I can do is my best. And if He's all He's cracked up to be, I imagine He can work through or in spite of my modest abilities and meager faith.- James 1:5-8

[+/-] Other Religions: A Conclusion |

Devoted readers may remember that one of my projects for this last year was looking into other religions. I had two goals: to better understand what attracts people to different religions, and to see if there was anything out there that suited me better than Christianity.

The answer to the second question, at this point, is no. I didn't do a great amount of attending services and whatnot, but I talked to a few people and took a couple classes and nothing leaped out at me.

Buddhism was the most appealing. I attended a couple of classes with a local Buddhist group and appreciated their practical focus and easygoing attitude. I like how Buddhism adapts to the needs of specific cultures, and its recognition that people are on different journeys, and what works for some people doesn't work for others. Regrettably, I found meditation extremely difficult and entirely ineffective. Perhaps I can be a Buddhist in my next life.

Judaism was very interesting, but also not my cup of tea. I doesn't help that many of my greatest difficulties with Christianity stem from the Hebrew Scriptures. Also, Jewish services are conducted largely in Hebrew, which I'm not particularly interested in learning.

I didn't look too deeply into Islam, but I learned three things that turned me off: Islam in general takes a very fundamentalist view of scripture, the Qur'an focuses on Hell much more than the Bible, and Islam is essentially political. It could never work out between us.

So the bad news is I haven't found anything I can really, whole-heartedly belong to. The good news is I'm becoming increasingly comfortable with who I am. I don't feel the need to fit into any specific category. I don't need to be a Christian or a Muslim or an Atheist or whatever. There are things about Christianity that resonate with me, and things that don't. There are aspects of other religions or worldviews or philosophies that seem meaningful or true to me, and I want to incorporate them into my beliefs and practices. I suppose I'm a Christian in the sense that I'm a member of a Christian community, and Jesus is probably the central figure in my worldview, but I don't have a desire to impose any specific boundaries around my spiritual or intellectual or moral life. I'm a pilgrim.

[+/-] I'm Not A Disciple |

I've recently begun thinking of myself as a disciple of Christ. I believe that Jesus called his followers not primarily to a belief system or a religion or a series of rituals, but to a lifestyle modeled after his own life and teachings.

The word "disciple", as I've said before, is not one that I'm entirely comfortable with. But I console myself that the original 12 were not spiritual supermen. At least, not initially. If a group of misguided, half-hearted, faithless, gutless, selfish outcasts can be disciples of Jesus, I figured maybe I'd fit right in.

But I was writing out Matthew 7 the other day (which gives you an idea of how slowly my project is going) and stumbled across the famous story of the wise and foolish builders:

This is the conclusion to the longest - and probably the most challenging - sermon recorded in the Bible. First Jesus says blessed are the meek and the mourners, and lust is as bad as adultery, and turn the other cheek, and love your enemies, and don't worry about where your next meal is coming from, and ask and it will be given, and (my personal favorite) be perfect, like God. Then he says, in effect, "follow my teaching, or you're headed for destruction". No wonder people were amazed."Therefore everyone who hears these words of mine and puts them into practice is like a wise man who built his house on the rock. ... But everyone who hears these words of mine and does not put them into practice is like a foolish man who built his house on sand."-Matt 7:24,26

I suddenly remembered that discipleship is serious business. You don't call yourself someone's disciple because you respect them, or you agree with them on certain points. A disciple is someone who is whole-heartedly committed to imitating and obeying his master. There are no part-time disciples.

Honestly, I don't agree with everything Jesus said. I agree with him more than most people in the Bible, but I'd be lying if I said I even wanted to submit to everything he taught. So I probably shouldn't call myself his disciple. At least, not yet.

[+/-] Lukewarm |

I'm sorry for not posting in a while. I've been feeling lazy and brain-tired. My scribing project is going slowly. Anyway, here's my most recent interesting thought:

I know your deeds, that you are neither cold nor hot. I wish you were either one or the other! So, because you are lukewarm—neither hot nor cold—I am about to spit you out of my mouth. You say, 'I am rich; I have acquired wealth and do not need a thing.' But you do not realize that you are wretched, pitiful, poor, blind and naked. I counsel you to buy from me gold refined in the fire, so you can become rich; and white clothes to wear, so you can cover your shameful nakedness; and salve to put on your eyes, so you can see.We looked at this passage in church last week. It's pretty tough stuff - "scary" is how someone put it - and it got me thinking about all the times in the Bible when God tells someone they suck. The prophets do a lot of that. Jesus spends a whole chapter railing on the Pharisees. There's the "Away from me evildoers" bit, and so on.-Revelation 3:15-18

Here's what I noticed: I can't think of a time in the Bible when God rebukes people who are already aware of/feeling bad about their failings. I think the Laodiceans' real problem wasn't that they were "wretched, pitiful, poor, blind and naked"; God has a solution for that. Their problem was that they didn't realize that they were wretched, pitiful, poor, blind and naked. They thought they were pretty good. Honestly, I'm not sure what is meant by "buy from me gold refined in the fire", etc. It seems that "wretched, pitiful, poor, blind and naked" is not the universal human condition, and that God expects us to transcend it, with his help. But I don't know how that works.

Anyway, it's comforting to think that God isn't angry with me for my wretchedness, and although he wants to see me cleaned up, he doesn't expect me to do it myself.

[+/-] I'm Tired and I Hurt All Over |

I took a bit of a tumble on Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs today. It was my first day of framing, and it was kind of long and quite grueling. I have a big post in the works, but it's only half-way thought through, and I'm not at all in the right frame of mind for that kind of thing. I fear I may not be my usual perspicacious self over the next couple months.

In other news, I'm finished the first five chapters of Matthew in my copy-the-New-Testament project. I've yet to go a full two pages without a scribal error, giving me new appreciation for those who carefully preserved these texts over the centuries. No profound insights yet, but so far the process has been considerably less tedious than expected. I would rather copy the Bible eleven hours a day than haul wood around, but I don't imagine I would make much money at it.

[+/-] Scrolls and Scribes |

The first time I saw a Torah scroll was in the special collections library at the University of Alberta. The scroll was beautiful. It was about three feet wide, made of parchment, and hand-written in ancient Hebrew, in strictly measured rows and columns. Like all Torah scrolls, it contained the first five books of the Hebrew Bible, and was written laboriously by a professional scribe over about a year. Like all scrolls, every line is the same length and contains the same words, and in every scroll there are precisely the same 304,805 Hebrew letters.

A new scroll will cost a synagogue something in the neighborhood of eighty thousand dollars. A synagogue's scroll is stored in an ark at the front, and every Sabbath it is taken out and carried up and down the aisles, and the congregants touch it with their prayer books, and then touch the books to their lips. The synagogues keep their scrolls in a beautiful fabric case, and decorate them with ornamental breastplates and crowns. I later learned that the University's scroll originated in what is now the Czech Republic, and is centuries old.

I felt a kind of awe when I saw this scroll for the first time. To be within a couple feet of something so old, so beloved and sacred, is quite an experience. Traditional Jews believe that the Torah was verbally inspired, word for word, to Moses on Mt. Sinai. They believe it was written at that time in the same form and the exact Hebrew letters and words in which it is now preserved, that the scroll I saw was a perfect preservation of the very words of Almighty G-d.

I've thought since then about the 17th century Czech scribe who wrote that scroll, and many others identical to it, one each year throughout his adult life. It's a very prestigious job, a high calling, but it must also be extraordinarily boring - a monotonous and meticulous process of copying 300,000 letters one by one, with exactly the right calligraphic flourishes.

I mentioned the scrolls and the scribes to a friend recently, and she decided she wants to write out the whole Old Testament by hand. I thought it was a great idea, but I doubt I have the patience to get through even the first five books. A good chunk of the Old Testament is unspeakably boring. But the New Testament might be manageable.

So on Thursday I bought a book with a black cover and thick, blank pages, and on Friday I bought two good pens. I won't follow the any of the strict rules of the Jewish scribes and I won't try to wrest my scrawl into an elegant script, but I will attempt to copy neatly and accurately the whole text of the NIV New Testament by hand.

I decided to do this for a number of reasons. For one thing, I hope it will help me develop patience and perseverance. I also hope that it will force me to read carefully through the text and not rush past the parts that don't interest me, or that I just don't like. I imagine it will be difficult for me to copy passages such as Romans 9, but maybe doing so will foster a sense of humility and reverence for the book. Maybe putting so much effort into the Bible will make it feel more meaningful or valuable or something. Or maybe I'll just get sick of it. I'll keep you posted.

[+/-] The Jews and Their Book |

I took a Judaism class this semester. I hoped that a Jewish perspective would shed some light on some of my many confusions and frustrations with the Bible, and especially the Old Testament. I've felt for some time that Christians (of course I don't mean all Christians) have a tendency to ignore or distort the more troublesome aspects of the Old Testament by emphasizing the supremacy of the New. How do we deal with a God who punishes whole nations, and even their slaves, for the sins of their kings? For many of us, it is enough that he doesn't seem to do these things anymore, and that Jesus was a really nice, gentle guy. Surely the God who demonstrated such love and grace in the New Testament would not do anything cruel or unjust, so however cruel and unjust his old-covenant actions seem to be, they must really be motivated by compassion or righteousness or some other good, Jesus-y quality.

This doesn't do much for me.

I hoped that Judaism could offer me some insight into what the troubling parts of the Old Testament are really saying. As direct heirs of the patriarchs, the judges and the prophets, without the benefit of our "New and Improved" Testament, they must have some insight into the more vexing aspects of the Torah. That was my reasoning.

It turns out that modern Judaism has very little in common with its Biblical roots. The destruction of the Temple in the first century brought an abrupt end to the religion of Moses, in which animal sacrifice was central. Modern Jews of all persuasions have immense reverence for the Torah (Genesis through Deuteronomy) but in practice, it is not their most authoritative text. Judaism today is largely the product of the centuries of Rabbinical debates and commentaries that form the Talmud. It is understood that the various, often contradictory positions of the Rabbis are inspired by God, and that it is the Rabbis' responsibility to continuously reinterpret and adapt Judaism to meet the needs of their time, culture, and individual congregations. (The relative value of adaptation and tradition is the primary difference between Reform, Conservative, and Orthodox Judaism.)

I was disappointed to hear that even the strictest Orthodox Jews no longer hold to many of the things that bother me most about the Bible. It's not that I think they should, really. I like the idea of continuous revelation. I think you could make a strong Biblical case for it, and I think it's more honest to say that we no longer believe certain things God has said because he reveals new things to new generations than to claim that we still believe everything God has said, and then twist or ignore the parts that don't fit with our modern intuitions. (I don't mean to suggest a dichotomy. I think there are other possibilities, but the latter approach seems to be quite popular among Christians.)

I was disappointed because I want to find someone who really believes in the God who sent the plagues on egypt, or who orders rape victims to marry their attackers, or who punishes children for their father's sins, to the four generations and beyond. I want find a champion for this God - someone who can explain why he should be worshiped or loved or believed in, or else who can explain to my satisfaction how these passages don't say what they seem to say. I don't know if I could be convinced that passages such as these are God-breathed, infallible truth, but I want to give them a fair shot.

My Judaism Professor said that much of the Torah is embarrassing to modern Jews. They certainly don't believe, for example, that God still commands genocidal war against immoral nations, but it is still problematic that, according to their scriptures, he used to. Jews, like Christians, seem to have found no good solution to this problem.

[+/-] A Hole of a Different Shape |

The LORD God said, "It is not good for the man to be alone. I will make a helper suitable for him."

...So the LORD God caused the man to fall into a deep sleep; and while he was sleeping, he took one of the man's ribs and closed up the place with flesh. Then the LORD God made a woman from the rib he had taken out of the man, and he brought her to the man.

The man said,

"This is now bone of my bones

and flesh of my flesh;

she shall be called 'woman,'

for she was taken out of man."

For this reason a man will leave his father and mother and be united to his wife, and they will become one flesh.-Gen 2:18-24

Something struck me today. The first couple chapters of the Bible describe God's "very good" creation, which included a man living in a very intimate relationship with God. God apparently had verbal conversations with Adam, gave him instructions, attended to his needs, and even walked in Adam's garden. This, according to the Bible, is paradise - the way God meant the world to be before the corruption of sin and death. But immediately (likely within minutes of Adam's creation, if you're a literalist) God senses that there's something missing.

"It is not good for the man to be alone."

In fact, Adam is not alone. God himself is near at hand - physically present. Few Biblical figures, and likely few people in history, have experienced anything like the kind of intimacy with God that Adam had. But it wasn't enough. Adam needed "a helper suitable for him."

I'm amazed by what this suggests about human fellowship. (It may also say something about gender roles, but I'll look past that for now.) I value my relationships, but I tend to think of them as a dim reflection of the relationship I hope to have with God. There may be some truth to this (particularly when human relationships are unhealthy) and I don't think friends or lovers were ever meant to fill my "God-shaped hole". But I think this passage suggests that there we also have "human companion-shaped holes" which even God Himself cannot adequately fill. That's pretty powerful statement about the importance of community.

[+/-] Fruit in Keeping With Repentance |

I've never been a huge fan of John the Baptist. I guess I've always envisioned him as a sort of first-century hellfire preacher - the sort of pulpit-pounding moralist who rails against miniskirts and alcohol and loud music. The kind who glares down at sinners and riffraff from beneath a furrowed brow, and yearns for the good old days when people wandered in the desert and wore camel-skins and were serious about God. You know the kind I mean.

John certainly sounds like a hard-ass. His slogan is "Repent, for the kingdom of heaven is near", which has a kind of a doomsday-prophet ring to it, and he greets the crowds who come to hear him preach as "You brood of vipers". He also warns that the Messiah will come and "burn up the chaff with unquenchable fire". Hard-ass.

Normally when I think of John I don't get much past the call for repentance and the "brood of vipers" line. But we get a glimpse into the content of his preaching (i.e. what he calls for repentance from and to) in Luke 3. John tears into the crowd for not "producing fruit in keeping with repentance", and the people ask him what exactly he wants them to do.

John answered, "The man with two tunics should share with him who has none, and the one who has food should do the same."

That's interesting. The crowds may have expected John to mention clothes and food, but he doesn't seize the opportunity to tell the them what kind of tunics they ought to wear (ankle-length, I would imagine, and preferably a coarse, itchy fabric) or which foods they shouldn't eat (the Jewish law is big on dietary restrictions, and John himself ate only locusts and honey). Instead he calls for compassion and charity. From this one comment, you'd almost get the idea that the coming kingdom is less about laws and purity and more about social justice. And it goes on.

Tax collectors also came to be baptized. "Teacher," they asked, "what should we do?"

"Don't collect any more than you are required to," he told them.

Then some soldiers asked him, "And what should we do?"

He replied, "Don't extort money and don't accuse people falsely — be content with your pay."

I'm struck by the practicality of John's teaching. Ethical business practices. Justice. Honesty. Compassion. These are the fruits of repentance. John seems to have no interest in long lists of religious laws. (He seemed to get along with those who kept them no better than did Jesus, and for the same reasons.) He also doesn't seem to care about respectability or avoiding the appearance of evil - after all, he never tells the tax collectors and soldiers to quit their disreputable jobs, only to do them with integrity. And he certainly didn't focus on matters of doctrine.

John's a real turn-or-burner, but at the same time he's radically compassionate. His style isn't quite to my liking, but his message, I think, is bang-on.

On a related note, I couldn't go through all of Lent without linking to Isaiah 58.

[+/-] Forgive Us Our Debts |

"This, then, is how you should pray:

...Forgive us our debts,

as we also have forgiven our debtors.

And lead us not into temptation,

but deliver us from the evil one.

For if you forgive men when they sin against you, your heavenly Father will also forgive you. But if you do not forgive men their sins, your Father will not forgive your sins."Matthew 6:9-15

Someone read this is church last week and I was struck by how strongly Jesus commands us to forgive. He goes so far as to say that God will forgive us if and only if we forgive others. Of course, other passages suggest that the requirements for God's forgiveness are far more complex, but this is not the only place where Jesus indicates that there is a relationship between forgiving and being forgiven.

"Then the master called the servant in. 'You wicked servant,' he said, 'I canceled all that debt of yours because you begged me to. Shouldn't you have had mercy on your fellow servant just as I had on you?' In anger his master turned him over to the jailers to be tortured, until he should pay back all he owed.

"This is how my heavenly Father will treat each of you unless you forgive your brother from your heart."Matthew 18:32-35

"And when you stand praying, if you hold anything against anyone, forgive him, so that your Father in heaven may forgive you your sins."Mark 11:25

"Do not judge, and you will not be judged. Do not condemn, and you will not be condemned. Forgive, and you will be forgiven. ...For with the measure you use, it will be measured to you."Luke 6:37-38

I'm not suggesting that we take these statements at face value (as I said, other passages suggest a more complex view) but I think we can say with certainty that Jesus viewed forgiveness as a discipline of the highest importance. I'm surprised that I haven't heard more about this. I can't remember ever hearing an alter call that included an admonition to forgive others. I don't recall ever hearing a sermon on Matthew 6:15, or reading "forgive and you will be forgiven" in a statement of faith. I'm sure no one would argue that forgiving others is unimportant, but I didn't realize that Jesus considered it so important. Food for thought.

[+/-] Trembling Before G-d |

We watched this movie in my Judaism class yesterday.

We watched this movie in my Judaism class yesterday.

It's about homosexual Orthodox and Hasidic (i.e. super-conservative) Jews struggling to reconcile their sexuality with their religious beliefs. It follows several people, including a man dying of AIDS and rediscovering his Orthodox roots, a lesbian couple who've been together for twelve years, the world's first openly gay Orthodox rabbi, and an ultra-orthodox, married Israeli woman who dares not tell her husband she's a lesbian. It also includes the perspectives of several Orthodox rabbis who struggle to find a balance between upholding their religious laws and showing compassion and acceptance to people in pain.

I found the movie moving and very thought provoking. It's not pro-gay propaganda, it offers no pat answers, and it's definitely worth watching even if you're not gay or Jewish. I borrowed the movie from my professor until Tuesday, so if you're in town and want to see it, give me a shout. I may purchase my own copy.

[+/-] Credo |

Blessed art I, the Lord thy God,

King of the Universe,

Who conveniently hateth thine enemy.

Who sanctifieth thy unsavory whims,

And justifieth whatever the fuck

you felt like doing anyway.

That's a bit from Credo, a short film that you can watch here. (Thanks to rlp.) The lyrics are here.

Regarding the film's major theme (the quote at the top isn't directly related) I'm not sure what I think of the idea that God cannot see the future, that he fails to understand the consequences of his actions, that he does not always do the right thing. It certainly explains a lot, about both the world we see around us and many troubling Bible stories. (The Bible never says God is all powerful, and what it does say about God changes an awful lot.) But it's a very frightening thing to consider.

[+/-] Without Excuse |

The wrath of God is being revealed from heaven against all the godlessness and wickedness of men who suppress the truth by their wickedness, since what may be known about God is plain to them, because God has made it plain to them. For since the creation of the world God's invisible qualities — his eternal power and divine nature — have been clearly seen, being understood from what has been made, so that men are without excuse.- Romans 1:18-20

Suppose we accept Paul's claim that creation reveals the "invisible qualities" of God. What would these qualities be? Of course we all see the world differently, and our religious beliefs influence our view of nature at least as much as nature influences our religious beliefs. It's hard to say what we might see if we looked at the world with fresh eyes, but we can make an educated guess by considering the beliefs of primitive religions, which are based primarily on observation of the world rather than supposed revelation. I'm not an anthropologist, but from my limited and perhaps inaccurate knowledge of the matter I have to following objections to Paul's claim:

1. The range of beliefs about among nature-based religions is vast. Thus the list God's qualities which are "plain" to everyone will be very short. Paul suggests that humanity in general has scorned the plain knowledge of God that nature provides, so someone may argue that those primitive religions which have very unbiblical understandings of God (the overwhelming majority) have intentionally ignored or distorted the natural evidence. I would reply that the unbiblical beliefs of nature-based religions make a lot of sense, and that belief in the biblical God is distinctly unnatural - that is, unlikely to result from simple observation of nature. This will be more clear in subsequent points.

2. Monotheism (belief in one god) seems to be quite unpopular in nature-based religions. Polytheism and pantheism are far simpler explanations for the immense diversity of nature and the plethora of forces (creation, destruction, nourishment, illness, etc.) at work in the world. Judging from nature, if there is only one god, he seems to be schizophrenic. I think it would be very difficult to argue that nature itself, apart from any religious, social, or scientific frameworks, points to a single God.

3. It seems to me that most primitive religions center around either appeasement or manipulation of the gods. The world is filled with suffering, which strikes seemingly at random. It is a basic human intuition that suffering is the result of the gods' displeasure, and the general brutality of nature suggests that the gods are easily angered. My understanding is that most primitive religions view the gods as either angry, vindictive beings who demand fear, strict obedience, and sacrifice, or as petty magicians to be bribed or manipulated for personal benefit. Although the biblical God does seem to have a vindictive streak, I think the God Paul is thinking of differs vastly in terms of both "his eternal power and divine nature" from the sorts of gods that are generally inferred from creation.

If you resist the idea that nature suggests a much crueler or much less powerful god than the Bible's, consider the first chapters of Genesis. The very first thing the Bible tells us is that the world we currently inhabit is not an accurate reflection of God's personality. Our world (according to Genesis) is full of suffering not because God is weak or sadistic, but because humans messed it up. Without this crucial information, you'd expect people to get a very different impression of God from nature.

4. A major theme in the Bible is the question of why a good God would allow the righteous to suffer and the wicked to go prosper. This is an excellent question, and it springs from the recognition that the world we inhabit does not seem to be governed by a powerful and just God. This puzzle eventually led to the concept of an afterlife (which developed between the Testaments, and not from divine revelation) in which we are finally repaid justly for our earthly works. The Jews, like all peoples, recognized that nature does not bless the meek, and from our worldly experience alone we have every reason to believe that the gods are indifferent to morality, or that they merely help those who help themselves. It may be true that all people have some moral code within them, but I don't believe nature suggests that the gods value this code.

It seems to me that the qualities of God that can be "clearly seen" in nature are in fact quite different from those clearly seen in the Bible. Paul, of all people, should know that the truth of Christianity is not self-evident, even to those with the benefit of familiarity with God's prior works.

[+/-] His Love Endures Forever |

Give thanks to the LORD, for he is good.

His love endures forever.

To him who struck down the firstborn of Egypt.

His love endures forever. - Psalm 136:1,10

What a bizarre thing to say. From my perspective, killing children is not a demonstration of love. I would call it cruelty, murder, perhaps genocide.

I suppose the author considered God's love (particularly his enduring love) to be more or less exclusive to Israel. The killing of every firstborn male in Egypt for the sake of Israel is seen as a cause for celebration and worship. This idea that's God's love is foremost or exclusively for the chosen people (chosen, not more obedient) crops up often in the Old Testament. Malachi even tells us we can see God's love by comparing Israel to those he hates.

I've mentioned before (point 5) that nations in the Bible seem to be only as good or evil as their kings. When righteous kings rule, the people are obedient and God blesses them. When wicked kings rule, the people are wicked, and God pours out his wrath upon them. I somehow doubt that all the people of a nation suddenly became moral or immoral when a new king was crowned; more likely the rise of a wicked king meant that the wicked people became wealthy and powerful, and with the rise of a righteous king they were killed or removed. Unless human nature has changed drastically since Bible times, I can't believe that there was ever such a thing as a wicked or righteous nation, only nations in which the ruler allows either wickedness or righteousness to prosper. If this is true it seems horribly cruel and unjust for God to bring judgment on a nation like Egypt. There was never a referendum on whether to let God's people go, and even if the majority of the Egyptians were resolutely opposed (which they weren't, as we'll see) the minority would not deserve continued judgment. (Someone might argue that God judges nations as a whole because it is not possible for him to pick a specific kind of person, such as "the wicked", out of a group and kill only them, but Exodus says that it is.)

But it gets worse. The Bible says that God "hardened Pharaoh's heart" so that he would refuse to release the Israelites. I've heard people defend God by claiming that first Pharaoh hardened his own heart several times, and then at a certain point God started hardening it for him. This is supposed to show that if you rebel against God for too long, eventually he gives up on you and makes you an object of his wrath or something like that. (So much for "His love endures forever".) Aside from not addressing the problem of judging a whole nation for its ruler's irrational obstinacy, the main problem with this claim is that it's not true. God planned to harden Pharaoh's heart right from the start. Look:

The LORD said to Moses, "When you return to Egypt, see that you perform before Pharaoh all the wonders I have given you the power to do. But I will harden his heart so that he will not let the people go. Then say to Pharaoh, 'This is what the LORD says: Israel is my firstborn son, and I told you, "Let my son go, so he may worship me." But you refused to let him go; so I will kill your firstborn son.'" - Exodus 4:21-23

And He says it again. (This is still before Moses has come before Pharaoh for the first time.)

"You are to say everything I command you, and your brother Aaron is to tell Pharaoh to let the Israelites go out of his country. But I will harden Pharaoh's heart, and though I multiply my miraculous signs and wonders in Egypt, he will not listen to you. Then I will lay my hand on Egypt and with mighty acts of judgment I will bring out my divisions, my people the Israelites." - Exodus 7:2-4

Sure enough, Pharaoh's heart is hardened. This is referred to at least a dozen times between Exodus 7 and 14. Sometimes it says Pharaoh hardened his heart, and sometimes it simply says that his heart became hard, or was hard, but mostly it says that God hardened his heart. I suspect that the writer of Exodus doesn't pay particular attention to who was responsible for each instance of hardening. The point seems to be that both Pharaoh and God are responsible.

It's strange that God goes through this long, brutal charade of demands and plagues and heart-hardening. The text seems to indicate that at several points God's hardening of Pharaoh's heart actually prevented Israel from being released, so clearly all this suffering is not an unfortunate-yet-necessary means to the deliverance of Israel. It seems that God's only reason for sending at least the last three plagues (those that occur after the last mention of Pharaoh hardening his own heart) was to demonstrate his power. God killed thousands of children just to prove that he could. And it gets worse:

Every firstborn son in Egypt will die, from the firstborn son of Pharaoh, who sits on the throne, to the firstborn son of the slave girl, who is at her hand mill, and all the firstborn of the cattle as well. - Exodus 11:5

If the death of a child was a just punishment (which it isn't, according to the God of Ezekiel), the death of Pharaoh's firstborn might be considered just. You'd have to argue that it was punishment for his general cruelty, rather than for his final, God-forced refusal to free the Israelites, but we'll let that pass for now. It might even be possible to argue that the Egyptians in general deserved this punishment for their cruelty towards Israel, although I would vehemently disagree. But what possible reason could God have for killing the sons of slave girls?

Forget about God hearing the cries of the oppressed. That's not what this is about. Far from concerning himself with their liberation, God is perfectly willing to bring suffering and destruction on Egypt's non-Jewish (i.e. non-Chosen) slaves. I suppose the reason is that the death of their firstborn slaves, along with their livestock and their own sons would make a more impressive demonstration of God's power for the Egyptians. That's God's goal here.

Bear in mind that by the time the tenth plague rolls around, no one wants the Israelites in Egypt anymore. The Egyptians have been made "favorably disposed" to them. (Which seems to mean scared to death.) Even Pharaoh's officials are urging him to let them go. And the Israelites themselves are still in slavery. The only one who's interested in delaying the exodus is God, who is intent on further proving his power by killing children.

By the way, I've often heard the argument that God refrains from performing great miracles in our time because of his great respect for human free will. The idea is that if God openly and miraculously intervened in our world, we would be forced to believe in Him. I have several objections to this argument. Is simply believing in God's existence what He wants from us? Isn't it obedience? Disbelief in the existence of God is quite a recent development; did humans have less free will before the advent of atheism? And most importantly, where is this concern for free will in the Bible? Jesus doesn't refrain from performing miracles for fear that it might force someone to believe in him. Signs and wonders are a staple of evangelism is Acts. And in the Old Testament, miracles are continuously performed not in spite of but for the purpose of proving the existence and power of God. (Remember Mount Carmel?) Here in Exodus, not only is God not concerned that his miracles will compromise free will, but he repeatedly overrides Pharaoh's free will in order to to preform more spectacular (and more horrible) miracles, and he does this explicitly for the purpose of proving his existence and power.

It astounds me that God did not simply kill Pharaoh himself, and anyone else who would prevent Israel from leaving. This would be more effective, more just, at least as easy and no less spectacular than killing firstborn sons. Why target children? That's movie-villain stuff. Even in war, the death of children is a ghastly thing, and anyone with a shred of decency will try to avoid it. That God kills thousands of people at the same time, and kills only firstborn males, and kills every one of them except those in houses with lambs' blood on their door, shows that He strikes with a precision that no earthly force could dream of. That He directly targets not those who deserve punishment or those who present and obstacle to the freedom of his people but children, even the children of slaves, and that he planned to do this from the beginning, and hardened his adversary in order to make this possible, and did it simply to demonstrate the magnitude of his power, makes him a monster.

To clarify, I do not believe that God is a monster. I believe in a good and compassionate God; a God whose love endures forever. But I do not believe that the God described here and in similar Bible stories is my God. (If you think this is an isolated incident, see Joshua 11.) It amazes me that anyone can believe in the God described by Moses and Joshua. It amazes me even more that people can describe this God as loving.