[+/-] Heck No At All! |

I was talking to a friend the other night about some of my recent entries and I realized he had entirely the wrong impression of why I think about what I do. At least, he and I disagreed, and I realized that I hadn't made my position as clear as I thought I had. So this is to explain why I write about the dark side of God and such things.

This will sound pretentious, but I read something in Plato's Republic that's analogous to my situation. The character Glaucon challenges Socrates, the protagonist, with a fairly persuasive argument in favor of living unjustly. Glaucon (wonderful name) stresses that he does not agree with the argument he's presenting - he believes, or wants to believe, that justice is superior to injustice - but he has not yet heard an argument in favor of justice that is as persuasive as he would like it to be. For this reason, he presents Socrates with an argument against justice that is as strong as he can make it and challenges Socrates to overcome it, hoping, of course, that he can.

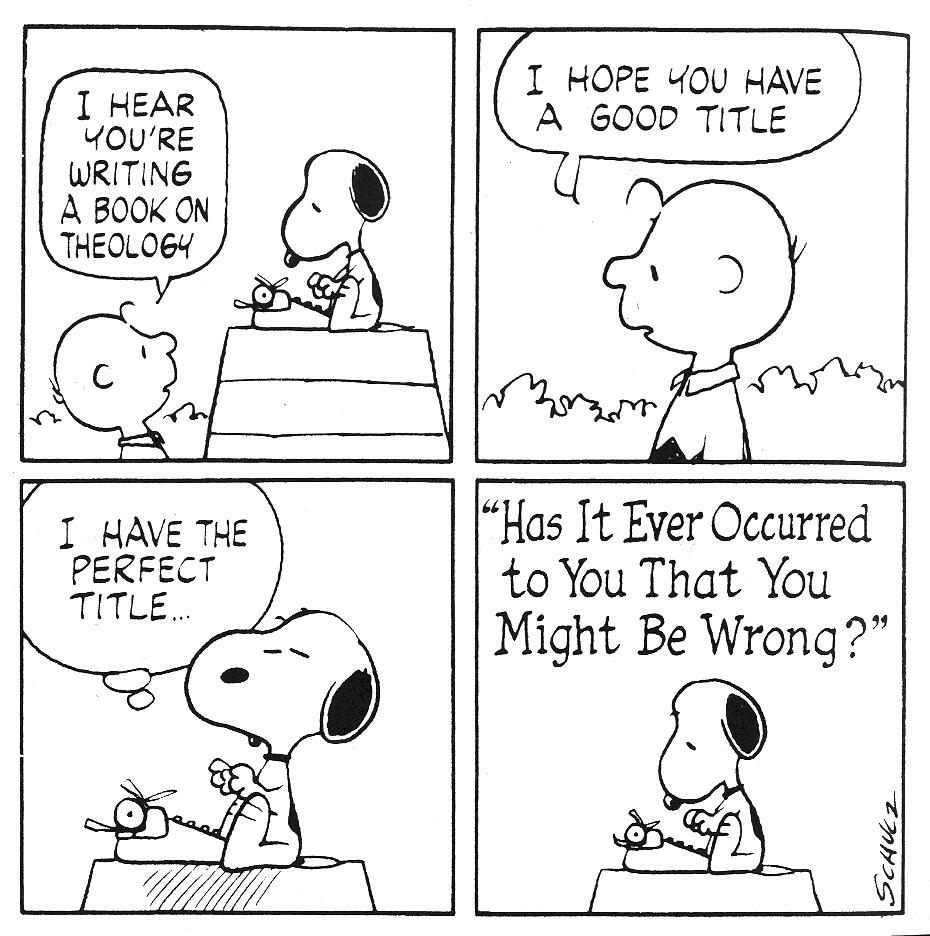

I hope (I'm not certain) it's clear to the reader that I don't have a vested interest in proving God to be unjust. Where would that get me? I really want God to be just, in fact I would do almost anything to continue to believe in God's justice, except ignoring or shrugging off evidence against it. I have long held the conviction that if I am to truly and resolutely believe in something, I must subject it to serious scrutiny. Not a mock-trial. Not a perfunctory, cursory scan of the evidence. I'm talking about honest, diligent examination.

This is why I sometimes write about the wrath of God and other things unbecoming of a devout Christian. Because I don't know anyone else who does, and I take my faith seriously enough to want to discover, to the best of my abilities, whether my beliefs are contradictory or flawed. I have no beef with those of you who find fault in my arguments (that's half the reason I blog) or the presentation thereof. But for those of you who think I'm an apostate, a God-mocker or a recreational doubter, hopefully this clears a few things up. If you still object to the questions I ask, I'm quite willing to discuss this further. And if you still object after that, no one's forcing you to read my blog.

I just remembered I wrote something similar to this a few months ago. I rather liked that post.

[+/-] The God of Wrath |

By now you've probably heard at least one fundamentalist group claim that the flood is God's judgment against New Orleans for Mardi Gras and other such wickedness. Various people have brought these claims to my attention, expressing their horror, disgust, disbelief and so forth, both at the idea of God destroying a city out of wrath and at those who have the heartlessness and gall to suggest it.

These claims of judgment immediately reminded me of a book of apologetics I browsed over the summer (Evidence that Demands a Verdict), specifically the chapter detailing the fulfillments of certain Biblical prophesies. These prophecies turned out to be almost exclusively about the violent destruction of wicked cities.

A quick scan of the prophetic books of the Old Testament reveals a remarkable fixation on judgment. One who reads these books might be forgiven for thinking that God spends most of his time pouring out wrath on immoral cities and nations. In a similar vein are the stories of the great flood in which God drowned all of mankind, the incineration of Sodom and Gomorrah, the ten plagues on Egypt, Joshua's genocidal conquest of the Promised Land, David's raiding parties (in which he left no woman or child alive), and the mass killing at the climax of Esther. If you read through the Bible it's hard not to notice God's habit of pouring out destruction on cities and nations as a whole (to say nothing of punishing children for their father's or even distant ancestor's sins). Mention this to most Christians and they'll tell you something about how God is just, or how it would be wrong not to punish evil people for their wrongdoing, or how actions have natural consequences...

Maybe you think the Egyptians (all of them, as a race) had it coming to them for enslaving the Israelites. Maybe you can explain why it was necessary or even compassionate for Jewish warriors to wipe out whole tribes, down to the last woman and child. Maybe you believe that we are "fallen" and God is holy, and this somehow gives him the right to wipe out "evil" cities. Maybe in your mind this is enough for Tyre, Sidon or Ashkelon. Is it enough for New Orleans?

Watch the News. See destruction. See grief. See the dead, the dying and the desolate. See the rich in safety and the poor in misery. See the statistics, and then see the people who make them up. See chaos. See despair. See the ruin and carnage created by a hurricane - an "act of God". Drink it in, feel it, and then tell me that a good and righteous God is punishing these people for their wickedness.

I don't believe you can. And I don't believe you could praise the God who destroyed Tyre, Sidon or Ashkelon, if you had been there. If you could see in the pages of your Bible what you see on the nightly news, if the genocide and destruction could be real to you, I think you would take a different view of Christianity and it's God. Your Bible stories are the stories of New Orleans, South-East Asia, September 11th, Somalia, Rwanda and the Holocaust, told by those who claim catastrophes as the judgment of an vengeful God. Your Bible is soaked with the blood of the dead and the doomed. You Bible is the chronicle of the conquests of the Lord of Hosts.

I cannot tell you if Katrina is the wrath of the Christian God. But I can tell you that He has orchestrated countless similar disasters. Do not forget this, Christian. Do not ignore it or excuse it or conceal it. You must deal with this fact if you believe your Bible: your God is a god who slaughters nations, destroys cities, and takes vengeance on children for their father's sins. Your God is a god of wrath.

Tell me, Christian, (because I carry this same burden) how do you deal with this knowledge?

[+/-] Jacob Returns |

Hello, I'm back. I've been more or less computerless for the past few weeks. I've had an awesome time doing entirely non-computer related things, but I'm glad to be blogging again.

So I ended up counseling for the final week of the summer, which was totally unexpected. Ever since the camp first contacted me in January, we've agreed that I shouldn't counsel, because we disagreed on some fairly foundational points of doctrine (inerrancy of scripture, damnation for all non-Christians, etc.). But they were in desperate need of another counselor for the final week, and I decided that maybe I could do it after all. To my surprise, they agreed. I'm not very good at guessing God's will, but it seemed like an interesting coincidence to me. If the issue had come up three days earlier, I'm sure I would have never considered asking to counsel. What changed? I'd been thinking the previous few days about what I believe, and this is roughly what I'd come up with:

As a child, I defined my spirituality by my beliefs. A Christian for me was someone who held all of the correct views on matters of theology, ethics, church practice and so on. A couple years ago when my beliefs began to change, it seemed like a terribly significant occurrence. Like anyone whose faith centers on his creed, I was shaken to find that it is possible for honest beliefs to change. Of course, my changes of perspective presented a huge problem when I wanted to work with various organizations whose statements of faith clashed with mine. I thought it was impossible for people to work toward a common goal when they differ in their beliefs about such important issues as women's roles, the importance of baptism, or the chronology of the end times. Just recently I've started to think that maybe all of these issues are secondary. So here's my statement of faith:

I believe in love, first and foremost. By 'love' I mean a change of focus from ourselves to others, selflessness, others-centeredness, compassion, servanthood, self-sacrifice. I believe in the ability of love to transform both the giver and the receiver. I believe that love is the catalyst for joy, for righteous living, and for every good thing. I believe love is the beginning of everything, the reason for everything, the goal of everything. I believe that the purpose behind the universe, the existence of mankind, all of history and every act of God is the creation of a community of love.

I am one who pursues love, first. I am a Christian second, and I am a Christian because what Christianity says about love makes sense to me. I attach little value to Christian beliefs or practices, except to the extent that they nurture or demonstrate love.

I believe that I can work with people whose beliefs and practices differ from my own so long as the goal of their ministry is love, and I believe (though I respect those who disagree) that my identity as a Christian and as one who pursues love qualifies me to work with other Christians.

I wrote recently that I've been thinking of finding a new group of people with which to serve and fellowship - people who believe stuff more similar to what I believe. Now I'm thinking that maybe I can still be a part of the more conservative group I've grown up in, because maybe our unity of focus is more important than our differences of doctrine. We'll see how it all plays out.

I start school in twelve hours. It's good to be back.

Post a Comment

5 comments:

Post a Comment